10.6 Judicial patent proceedings and case management

Prior to the mid-1990s, U.S. patent case management practices varied significantly across federal district courts. Busy federal judges improvised patent case management, leading to confusing and costly proceedings. In many respects, federal district judges operated as silos across a wide landscape.134

Moreover, the growing use of juries complicated both patent trials and appellate review. In most jury trials, the district judges did not construe the patents themselves but rather instructed the juries to resolve claim construction disputes as part of their deliberations. Since juries did not explain their claim construction in rendering their verdicts, this practice shrouded the jury’s claim construction determinations, making jury patent decisions especially difficult to review. This problem precipitated major changes in patent case management.

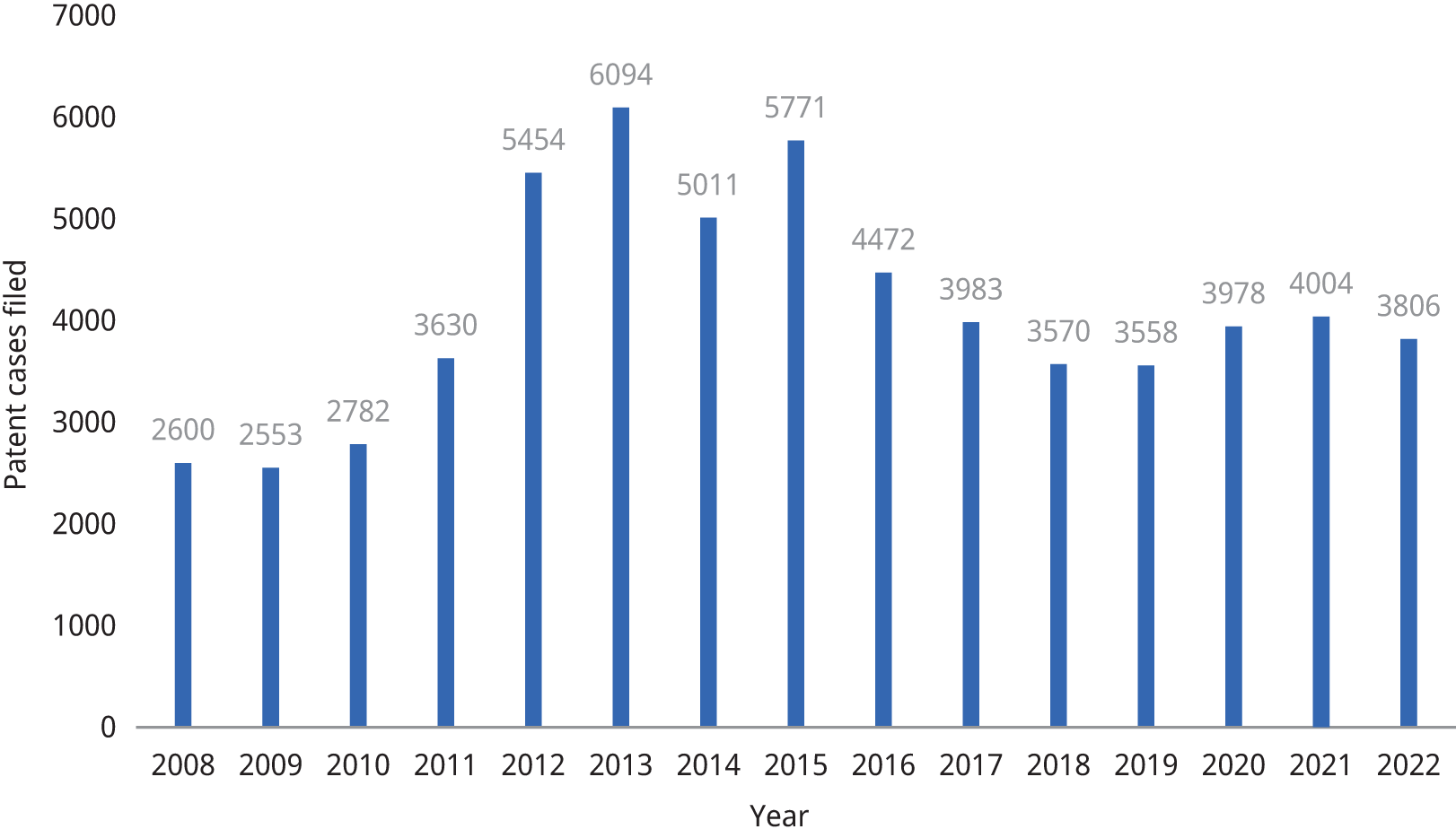

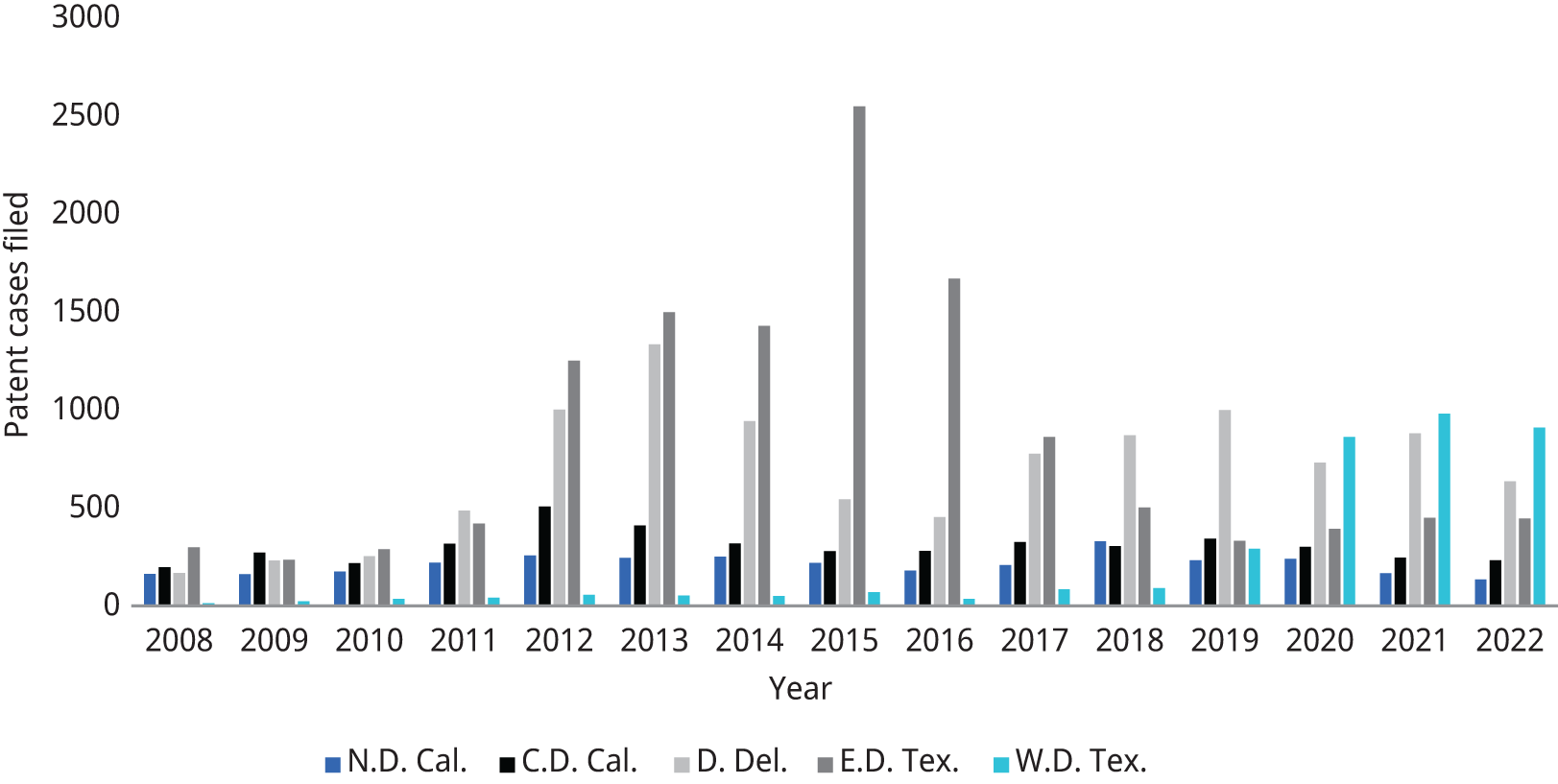

Figures 10.6 and 10.7 show the total number of patent cases filed across all U.S. district courts from 2008 to 2022, and the number of patent cases filed in certain U.S. district courts with a significant number of patent cases during this same time period (Northern District of California (N.D. Cal.), Central District of California (C.D. Cal.), Delaware (D. Del.), Eastern District of Texas (E.D. Tex.), and Western District of Texas (W.D. Tex.)).135 These statistics reflect the growth of patent case filings nationwide during this time period, as well as the concentration of a large number of these cases in the jurisdictions shown.

Figure 10.6 Total U.S. district court patent case filings (2008 to 2022)

Figure 10.7 Patent case filings in certain U.S. district courts (2008 to 2022)

Figure 10.7 Patent case filings in certain U.S. district courts (2008 to 2022)

10.6.1 Key features in patent proceedings

In 1996, the Supreme Court held that “the construction of a patent, including terms of art within its claim, is exclusively within the province of the court.”136 This decision ushered in a new patent case management era, elevating claim construction to a critical and central role in patent litigation. In the aftermath of this decision, Judge Ronald Whyte promulgated “patent local rules” (PLRs) in collaboration with patent litigators for the Northern District of California in 1998. These voluntary case management schedules structured discovery, specified deadlines for infringement and invalidity contentions, and prioritized claim construction. Many other district courts adopted these or similar patent case management rules, leading to more streamlined and consistent practices. The following sections explain these and other district court patent case management practices in nonpharmaceutical patent cases. Section 10.13.2 discusses patent case management in pharmaceutical patent cases.

10.6.2 Pre-trial

A patent case is, in many ways, like other civil cases. In most patent cases, the plaintiff files a complaint alleging infringement. The defendant answers the complaint, alleging noninfringement and asserting various defenses, and potentially makes counterclaims of its own. The parties proceed to fact and expert discovery, motion practice, pre-trial briefing, and trial.

As in any litigation, the time necessary for each pre-trial phase varies with the complexity and potential consequences of the issues presented. There are, however, various unique aspects of patent litigation for which case characteristics and management approaches significantly affect the pre-trial timeline. Key among these are the complexity of the legal issues, the intricacy of the technology at issue, and the volume of highly sensitive technical documents, source code and other information exchanged during discovery.

Due to the many challenges posed by patent cases, many district courts and district judges have developed specialized PLRs to streamline discovery, require parties to disclose and narrow contentions, and facilitate claim construction. These rules produce joint, sequenced, staged, and timely disclosure of critical information without the need for significant judicial oversight.

10.6.3 Venue, jurisdiction and case assignment rules

Many patent litigants place tremendous significance on the choice of venue due to the range of patent case management practices, judicial assignment procedures, speed of case processing, geographical convenience for evidence and witnesses, and composition of jury pools. Most district courts assign cases randomly to judges within the district, but a few district courts allow cases to be filed in a particular courthouse. Where only one district judge sits in that courthouse, plaintiffs can effectively select not only a particular district but also a particular judge. This has led to controversy over the large number of cases brought in just a few district courts outside of the defendants’ state of incorporation and principal locations of operations.

Federal law provides “[a]ny civil action for patent infringement may be brought in the judicial district where the defendant resides, or where the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business.”137 Regarding the first prong of the venue statute, the Supreme Court has clarified that a corporation “resides” only in its state of incorporation.138 The Federal Circuit interprets the second prong of the venue statute to require three elements: (1) there must be a physical place in the district, (2) it must be a regular and established place of business, and (3) it must be the place of the defendant.139

Even where venue is authorized, defendants can seek a change in venue by filing a motion early in the litigation process based on “the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice.”140 FRCP 72(a) requires that district courts “promptly conduct” venue transfer proceedings.141 In determining whether to transfer venue, courts balance the convenience of the litigants and the public interest in the fair and efficient administration of justice. The convenience factors include (1) the relative ease of access to sources of proof, (2) the availability of the compulsory process to secure witnesses’ attendance, (3) the willing witnesses’ cost of attendance and (4) all other practical problems that may interfere with the litigation being relatively easy, expeditious and inexpensive.142 The public factors include (1) the administrative difficulties flowing from court congestion, (2) the local interest in having local issues decided at home, (3) the forum’s familiarity with the governing law, and (4) the avoidance of unnecessary conflict-of-law problems involving the application of foreign law.143 The Federal Circuit may grant a writ of mandamus ordering a district court to transfer a case to a different venue to correct “a patently erroneous denial of transfer.”144

10.6.4 Alternative dispute resolution

The vast majority of patent cases (about 95 percent) settle prior to trial, but often not until late in the case. In the meantime, the litigation can be extremely expensive for the parties. Each side can expect to spend several million dollars in fees through the close of discovery, and between double or triple that amount in total through trial.145

Most parties to patent litigation recognize the high economic stakes, uncertainty, and legal costs involved. Nevertheless, various impediments to settlement – ranging from the relationships between the particular parties to institutional issues arising out of the nature of some patent litigation – often prevent parties from settling cases without some outside assistance. Consequently, district judges seek to motivate the parties to settle patent cases. Early judicial intervention, usually at the initial case management conference, can be a critical factor in bringing about settlement. Such initiative by the court emphasizes to the parties that the court wants them to actively consider settlement strategies as well as litigation strategies throughout the case.

Effective judicial encouragement of settlement involves several considerations: (1) appropriate initiation of mediation, (2) selection of the mediator, (3) scheduling of mediation, (4) delineating the powers of the mediator, (5) confidentiality of the mediation process, and (6) the relationship between mediation and litigation activities. Additional considerations come into play in multiparty and multijurisdictional cases.146

Many courts require, either by local rules or standardized order, that counsel for the parties discuss how they will attempt to mediate the case before the initial first case management conference and that they report either their agreed plan or differing positions to the court at the conference. District judges can order the parties to participate in mediation.147 By requiring this early discussion, the court eliminates any concern that the party first raising the possibility of settlement appears weak. This can be particularly important at the outset of a case when attitudes may be especially rigid, posturing can be most severe, and counsel may know little about the merits of their clients’ positions.

Courts can identify successful mediators for patent cases from a variety of sources: other judges and magistrate judges, retired judges, professional mediators and practicing lawyers. In some courts, the trial judge serves as mediator, but this requires the express consent of the parties.148 Many judges decline to act in this role for their own cases because they believe that it is difficult to have the requisite candid discussion with parties and their counsel and later objectively rule on the many issues the court must decide. In some district courts, magistrate judges serve as mediators.

To maximize open communication and candor, most district courts treat everything submitted, said, or done during the mediation as confidential and not available for use for any other purpose. Confidentiality is usually required by agreement of the parties or by court order or rule.149 Generally, the confidentiality requirements go beyond the evidentiary exclusion of FRE 408 to ensure that the parties, their counsel, and the mediator can candidly discuss the facts and merits of the litigation without concern that statements might be used in the litigation or publicized. This same concern for confidentiality usually precludes reports to the trial judge of anything other than procedural details about the mediation, such as the dates of mediation sessions, or a party’s violation of court rules or orders requiring participation. In addition to being confidential, briefing and communications relating to mediation may be privileged against discovery in future litigation.

10.6.5 Statements of case (pleading)

Under the liberal federal pleading rules in the United States, patent infringement complaints typically provide a statement of ownership of the asserted patent(s), identify the accused infringer(s), provide a brief statement of alleged infringing acts, and (if applicable) provide a statement regarding the patent owner’s marking of a product with the patent number under 35 U.S.C. § 287 (which affects potential monetary damages). The fleshing out of the allegations typically occurs as fact discovery unfolds and PLRs dictate.150 After that early disclosure, the asserted claims and accused products may not be amended without leave of court for good cause.151

Like the plaintiff’s allegations of infringement, the defendant’s allegations of invalidity need not be pled with particularity. Defendants typically recite only that the patent is invalid and may identify sections of the Patent Act related to their invalidity allegations. Although this sort of notice-pleading has usually been held to satisfy the FRCP, in practice, it gives little notice to a patent holder about what grounds for invalidity a defendant will actually assert. Consequently, some district judges require that defendants disclose the specific grounds on which they assert invalidity early in a case, just as they require specific infringement contentions from a patent owner. Courts can require defendants to identify specific prior art references they intend to assert as invalidating and to disclose invalidity claims based on written description, indefiniteness or enablement.152 Following a specified period for making these disclosures, they may be amended only upon a showing of good cause.153

With the exception of inequitable conduct, unenforceability allegations need not be pled with particularity. By contrast, inequitable conduct is seen as a species of fraud and must therefore be pled with particularity.154 Inequitable conduct must rest on specific allegations of intentional, material omissions or misrepresentations by the patentee during the application process for a patent.

The defendant typically asserts an array of counterclaims. In nearly every case, it seeks a declaratory judgment that the asserted patents are not infringed, invalid, and/or unenforceable. The defendant may also assert infringement of its own patents in a counterclaim. Under FRCP 13(a), a counterclaim is compulsory if it arises out of the same transaction or occurrence as the opposing party’s claim. A counterclaim for infringement is compulsory in an action for declaration of noninfringement. Similarly, counterclaims for declaratory judgment of noninfringement or invalidity are compulsory with respect to a claim of infringement.

10.6.6 Early case management

After the complaint is served and the case is assigned to a district judge, the parties and the court prepare for the initial case management conference.155 Since patent cases typically involve proprietary information, the court typically issues a protective order if the parties have not already agreed to one.156 Pursuant to FRCP 26(f), the parties must confer as soon as practicable – and, in any event, at least 21 days before a scheduling conference – to discuss:

-

the nature and basis of their claims and defenses and the possibilities for promptly settling or resolving the case;

-

making or arranging for mandatory initial disclosures (contact information for individuals with discoverable information, a copy of or description by category and location of all documents that support claims or defenses, a computation of each category of damages, and any insurance agreements covering possible judgment)157 and

-

a discovery plan.

Based on these discussions, the parties prepare and submit a Joint Case Management Statement to the court within 14 days of their meeting.

At the initial case management conference, the court and parties identify issues relating to the substance of the case and any business considerations that influence the dispute. In many districts, the conference is held off the record, with only counsel in attendance. Informality can promote more productive discussion and compromise. In particularly complex or contentious cases, some judges conduct the proceeding on the record.

In advance of the initial conference, many courts will issue a form of standing order that applies to patent cases, addressing the matters to be covered in the joint case management statement, the agenda for the initial case management conference, PLRs and attendant disclosures, and presumptive limitations on discovery. Some courts have found it helpful in patent cases to distribute a very brief “advisory” document to address some of the special aspects of patent litigation, as well as expectations for the conduct of the case, beyond what might be found in a typical standing order or in local rules. This advisory document may be distributed at, or in advance of, the initial case management conference.

Table 10.2 identifies subjects for initial and subsequent case management conferences that guide preparations for discussing the case. Exploring these issues provides insight into how counsel might be expected to conduct the litigation and whether the case is amenable to early settlement or summary judgment.

Table 10.2 Case management conference checklist

Technological, market, and litigation background

- Informal description of the technology

- Identity of the accused products

- Whether the primary basis for asserted liability is direct or indirect infringement

- Whether there are any third parties from which the parties expect to obtain substantial discovery

- Scope of accused products relative to the defendant’s business

- Scope of the patented/embodying technology relative to the patentee’s business

- Whether the parties are competitors

- Whether the patent(s)-in-suit have been, or are likely to be, the subject of reexamination proceedings

- Potential for parallel litigation and/or inter partes review

- Will a party seek a stay, consolidation, coordination or transfer?

- Identify patent eligibility (35 U.S.C. § 101) issues and discuss when they should be addressed

- What type of relief is being sought?

- What damage theory(ies) will be pursued? How will they be proven?

- Will injunctive relief be sought, and what kind?

- What are the estimated damages?

- What do the parties contend is the “smallest saleable patent practicing unit”? (relevant to damages)

- Is the patentee licensing the technology and when will it produce licensing information?

- Are any technology standards implicated? (relevant to standard-essential patents (SEP) and fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory agreements (FRAND))

|

Protective order

- Is a protective order needed?

- Will a standard protective order suffice, or will any party seek special requirements?

- Discuss known points of contention (e.g., prosecution bar, levels of confidentiality, and access by in-house lawyers) and, if applicable, convey the court’s general perspective on such issues

|

Willfulness

- Does the patentee intend to assert willful patent infringement? (relevant to enhanced damages)

- Timing of the assertion of the claim

- Timing of the reliance on any opinion of counsel

- Possibility of bifurcation

- Possibility of disqualification of counsel

|

Alternative dispute resolution

- Usefulness

- Timing

- Mediation, arbitration, or other form

|

Electronic discovery and limitations on discovery

- Format(s) for production of electronic discovery

- Limits on the scope of electronic discovery

- Source code – how will it be produced?

- Limits on the number of custodians

- Number of total hours for fact witnesses or number of depositions

|

Contention disclosures and schedule

- In patent local rule jurisdictions, discuss whether variance from the standard disclosure timelines is appropriate

- In jurisdictions without patent local rules, discuss whether the parties should exchange infringement, invalidity, unenforceability, and damages contentions and the appropriate schedule for such disclosures

|

Timing and procedures for claim construction and dispositive motions

- Determine the timing of summary judgment relative to claim construction

- If not addressed by local rule(s), set a schedule for exchanges of claim terms, proposed constructions, and supporting evidence

- Discuss whether a tutorial would be appropriate

- How is it conducted: by counsel? by experts? submissions (e.g., videos)?

- Number of patents and patent claims that would be tried and possible ways of winnowing (reducing number of claims)

- Limits on the number of claim terms submitted for construction

- Require an explanation of the significance of the term (e.g., effect on infringement/validity)

- Ask parties to rank the disputed claim terms based on their significance for resolving the case

- Logistics

- Identify disputed subsidiary factual issues

- Whether live witnesses should be called

- Use of graphics, animations or other visual displays to aid in understanding the technology and disputed claim terms

- Schedule a pre-claim construction conference to finalize the logistics for the hearing (held after the parties’ positions on claim construction have crystallized)

- Whether any summary judgment issues depend on claim construction or can otherwise be resolved with little or no discovery, including

- Is there a dispute about the structure and/or function of the accused products?

- Is there any claim term or claim construction issue that, once decided, will compel infringement or noninfringement?

- Are there territorial issues (e.g., location of allegedly infringing acts) that affect infringement?

- Are there any claims or defenses that are purely legal in nature?

|

Summary judgment

- Whether any limits on the number of summary judgment motions (or number of pages of briefing) should be imposed or modified

|

Limits on prior art references

- Whether any limits on the number of prior art references (per patent or overall) proffered by the defendant(s) should be imposed

- Timing for any planned reduction of the number of prior art references in the case

|

Expert witness and in limine (limiting evidence) motions

- Schedule expert witness exclusion (Daubert) motions well in advance of the pre-trial conference

- Scope of in limine motion practice

- Damages

- Whether it would be appropriate to require damages contentions, an expedited damages discovery schedule, and/or both, or to take other steps to facilitate the early resolution of challenges to damages-related theories or expert testimony

|

Following the initial case management conference, the court issues a scheduling order setting time limits for joining other parties, amending the pleadings, carrying out discovery, and filing motions.

10.6.6.1 Patent local rules

Early case management focuses on the winnowing of patent claims, the revelation of invalidity contentions, and the timing of claim construction. The Northern District of California developed a set of PLRs in the late 1990s to streamline the process for focusing the litigation. Although the rules were initially intended as guidelines, patent litigants and judges came to appreciate having default rules and the PLRs came to set case management into motion without objection in many patent cases. Many other courts have adopted these procedures. As a result, most U.S. patent cases are guided, if not governed, by a specialized set of procedural rules that supplement the FRCP.

PLRs require parties to crystallize their theories of the case early in the litigation and to adhere to those theories once they have been disclosed. Neither litigant can engage in a strategic game of saying it will not disclose its contentions until the other side reveals its arguments. By requiring parties to disclose contentions in an orderly, sequenced manner, PLRs counter the “shifting sands” tendencies of patent litigation, and provide more certainty for litigants and the court. In discussing the Northern District of California’s PLRs, the Federal Circuit explained:

[T]hey are designed to require both the plaintiff and the defendant in patent cases to provide early notice of their infringement and invalidity contentions, and to proceed with diligence in amending those contentions when new information comes to light in the course of discovery. The rules thus seek to balance the right to develop new information in discovery with the need for certainty as to the legal theories.158

PLRs focus on framing the court’s claim construction decision. As reflected in Table 10.3, the Northern District of California’s PLRs set forth a detailed timetable structuring the disclosure of asserted claims and infringement contentions, invalidity contentions, disputed claim terms, and damages contentions.159 These disclosures are made in conjunction with a concise claim construction discovery period and followed by a claim construction briefing schedule. These PLRs are designed to enable the court to conduct a claim construction hearing (often called a “Markman” hearing)160 seven months after the initial case management conference.

Table 10.3 Northern District of California’s patent local rules timetable1

| Stage |

Patent local rule |

Action |

Timing |

| 1 |

|

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(a) case management conference |

Set by the court |

| 2 |

3–1, 3–2 |

Disclosure of asserted claims and infringement contentions |

Within 14 days of Stage 1 |

| 3 |

3–3, 3–4 |

Invalidity contentions |

Within 45 days of Stage 2 |

| 4 |

4–1 |

Identify claim terms to be construed |

Within 14 days of Stage 3 |

| 5 |

4–2 |

Preliminary claim constructions |

Within 21 days of Stage 4 |

| 6 |

3–8 |

Damages contentions |

Within 50 days of Stage 3 |

| 7 |

3–9 |

Responsive damages contentions |

Within 30 days of Stage 6 |

| 8 |

4–3 |

Joint claim construction and prehearing statement |

Within 60 days of Stage 3 |

| 9 |

4–4 |

Close of claim construction discovery |

Within 30 days of Stage 8 |

| 10 |

4–5(a) |

Opening claim construction brief |

Within 45 days of Stage 8 |

| 11 |

4–5(b) |

Responsive claim construction brief |

Within 14 days of Stage 10 |

| 12 |

4–5(c) |

Reply claim construction brief |

Within 7 days of Stage 11 |

| 13 |

4–6 |

Claim construction hearing |

Subject to convenience of court, 14 days after Stage 12 |

| 14 |

|

Claim construction order |

Determined by the court |

| 15 |

3–7 |

Produce advice of counsel, if any |

Within 30 days of Stage 14 |

An accelerated timeline may be appropriate for less complex cases: for example, where the technology is simple or where there is little dispute as to the structure, function, or operation of accused devices. Under a particularly streamlined plan, the parties would not make patent-specific initial disclosures or file joint claim construction statements.

District courts have wide discretion to limit the number of claim terms at issue, at least provisionally. Restricting the scope of the claim construction hearing focuses the court’s attention on the key issues (which may dispose of the case) and allows a more prompt and well-reasoned ruling on the central matters in the case. Allowing the parties wide discretion to brief all claim terms that are potentially at issue invites false or inconsequential disputes. Parties reflexively seek to avoid the risk of a waiver finding if they refrain from raising all potential disputes.

10.6.6.1.1 Winnowing claim terms

To focus patent litigation on the most salient issues, many courts have established a presumptive limit on the number of claim terms – typically 10 – that can be presented at the claim construction hearing.161 The default 10-term limit can be increased or decreased depending on the circumstances of the case. In addition, some courts require parties to explain why particular terms are case-dispositive or otherwise significant so as to provide the court with context for the claim construction dispute as well as the basis for deciding whether early construction of particular claim terms is warranted. The 10-term limit does not fix the total number of terms that can be construed before trial; parties can seek to construe additional terms at later phases in the case. However, for purposes of the principal claim construction hearing, selecting the most significant terms allows courts to resolve the key disputes in the case most efficiently.

10.6.6.1.2 Winnowing prior art references

Just as the assertion of myriad patent claims unduly complicates patent litigation for the defense, the assertion of myriad prior art references – many of which will not be pursued – can impose undue costs on the patentee and the court. A court can, within its discretion, propose a phased process for winnowing the number of asserted prior art references in a matter.

10.6.6.2 Claim construction

Most courts conduct a half-day or full-day claim construction hearing at which the attorneys present tutorials and their proposed constructions and the judge can question them. Some judges will issue a tentative ruling prior to the hearing to signal their inclination and to focus the argument. Such tentative rulings are less feasible where the patented invention involves complex science and technology.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc.162 established that district courts may conduct evidentiary fact-finding to support their claim construction rulings. There is no requirement, however, for district courts to do so; they may base their rulings on evidence intrinsic to the patent, in which case the claim construction process is a question of law. District courts may also base their rulings on extrinsic evidence – such as documentary evidence that is not part of the patent file history; inventor or expert testimony; dictionaries; or treatises – in which case the subsidiary basis or bases are entitled to deference on appeal.

Most courts conduct claim construction hearings in an informal manner, applying the FRE loosely. Courts are generally circumspect about hearsay and allow the use of depositions instead of live testimony (so long as there has been an opportunity for cross-examination) and freer use of documents without a foundational witness (so long as there is no dispute about the document’s authenticity). This approach reduces the cost and burden of the hearing. District judges should, however, apply more careful procedures to the extent they intend to make factual findings so that their determination rests on a sound evidentiary record.

District judges must construe claim terms from the perspective of a person having ordinary skill in the art as of the time the invention was made. Since few, if any, district judges have such training and experience, the parties need to educate the court about the science and technology, and the perspective of a person having ordinary skill in the art as of the time of the invention. The most common vehicle for accomplishing this task is the use of technology tutorials either preceding or in connection with a claim construction hearing. Most claim construction hearings proceed with lawyer argument on a term-by-term basis. This can be presented by the attorneys or technical experts hired by the parties.

Some judges take a significant further step and appoint a technical advisor, special master, or expert for the court. The Federal Circuit expressly approved appointing a technical advisor for claim construction proceedings in TechSearch LLP v. Intel Corp.,163 although the court emphasized the need to establish “safeguards to prevent the technical advisor from introducing new evidence and to assure that the technical advisor does not influence the district court’s review of the factual disputes.”164 The technical advisor’s proper role is that of a sounding board or tutor who aids the judge’s understanding of the technology. This includes explaining the jargon used in the field, the underlying theory or science of the invention, or other technical aspects of the evidence being presented by the parties.

Some courts, pursuant to FRCP 53, have delegated initial consideration of claim construction to a special master. Such special masters often have general legal training as well as experience with patent law. They might also be familiar with the technical field in question. The special master will typically conduct a claim construction process with briefing and argument. The special master will then prepare a formal report with recommendations regarding the construction of disputed claim terms. After the parties have had an opportunity to object to that report, the court will often conduct a hearing at which the court may receive additional evidence and then adopt, reject, or modify the recommended claim constructions.

10.6.6.2.1 The claim construction ruling

The claim construction ruling becomes the basis for the court’s jury instructions and ultimate appellate review. In view of the jury’s lack of scientific and technical expertise, judges should require the parties to propose constructions in language that can be readily understood by juries. Courts should draft their claim construction rulings with an eye toward making the claim terms understandable to the jury. Moreover, the court is free to devise its own construction of claim terms rather than adopt a construction proposed by either of the parties. However, the consequence of the court issuing its own construction is that it may upset the foundations of the parties’ expert reports and any pending motions before the court. This problem may be particularly acute in late-stage claim construction hearings where the parties’ experts have already rendered reports based on the particular wording of the parties’ proposed constructions. In such circumstances, departing from the parties’ proposed constructions may throw a case off track by requiring new expert reports and a redrafting of case-dispositive motions.

There is no requirement that a court construe a claim term when there is no genuine dispute about its meaning.165 Claim construction aims to define the proper scope of the invention and to give meaning to claim language when the jury might otherwise misunderstand a claim term in the context of the patent and its file history. If a claim term is nontechnical, is in plain English, and derives no special meaning from the patent or its prosecution history, then the court need not function as a thesaurus. The “ordinary” meaning of such terms speaks for itself, and the court should avoid merely paraphrasing claim language with less accurate terminology.

10.6.6.3 Early case management motion practice

The FRCP authorize district courts to dismiss lawsuits for lack of personal jurisdiction166 or failure to state a claim on which relief can be granted.167 The district court may also grant judgment on the pleadings.168 In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decisions tightening patent eligibility (35 U.S.C. § 101) standards,169 some district courts have dismissed patent cases based on a pre-trial finding that the claims at issue were too abstract or lacked sufficient inventive application of laws of nature or natural phenomena. Two key questions in deciding whether to dismiss a patent case for failing to satisfy § 101 are (1) whether the determination that a claim element or combination of elements is well understood, routine and conventional to a skilled artisan in the relevant field is a question of fact, and (2) whether the patent eligibility determination requires claim construction.170

District courts can also dismiss patent lawsuits or requests for enhanced damages early in the litigation process where a critical element of the patent cause of action is absent. Indirect infringement and willful infringement (a key issue in damage enhancement) both require that the accused infringer knew of the asserted patents prior to the litigation. Indirect infringement is also predicated on an act of direct infringement. Therefore, claims of indirect infringement and willfulness are susceptible to early determination.

Indirect infringement claims frequently arise in cases involving patents with method claims. In these cases, a patentee’s only practical cause of action will often be for indirect infringement against the manufacturer of a product alleged to practice the method claim. In these circumstances, there are numerous ways in which a court can surface early case-dispositive weaknesses. For example, if no single entity is responsible for the performance of each step of the claim, it may be fatal to the patentee’s case.171 Alternatively, if the accused product is capable of many noninfringing uses and the manufacturer exerts no control over its customers, the claim will likely fail.172

10.6.7 Preliminary relief

Patentees may seek preliminary relief early in the litigation, although the burden is high. Section 283 of the Patent Act provides that courts “may grant injunctions in accordance with the principles of equity to prevent the violation of any right secured by patent, on such terms as the court deems reasonable.” Such preliminary relief can come in two forms: (1) a preliminary injunction, or (2) a temporary restraining order (TRO).

Preliminary injunction applications in patent matters present special challenges. Proving the likelihood of success on the merits typically calls for analysis of nearly every substantive issue that ultimately will be presented at trial. To address the merits, the court must at least preliminarily construe patent claim terms, and invalidity, infringement, and enforceability must be addressed based on those constructions. The patent holder has the burden of proof to demonstrate the predicates for a preliminary injunction. This includes the burden of showing that the asserted patents are likely infringed and the absence of any substantial question that the asserted patent claims are valid or that the patent is enforceable. The validity and enforceability determinations are made in light of the presumption of patent validity and that the accused infringer has the ultimate burden of proof on these issues at trial. To address harm, the parties often present complicated market analyses. These issues typically require both fact and expert discovery, undertaken on a compressed preliminary injunction schedule.

FRCP 65 sets forth the procedures governing preliminary injunction motions, and Federal Circuit law governs the analysis. While:

the grant of a preliminary injunction [is] a matter of procedural law not unique to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit, and on appellate review […] procedural law of the regional circuit in which the case was brought [applies], […] the general considerations underlying the grant or denial of a preliminary injunction do not vary significantly among the circuits.173

Consequently, the Federal Circuit has “built a body of precedent applying these general considerations to a large number of factually variant patent cases, and [it] give[s] dominant effect to Federal Circuit precedent insofar as it reflects considerations specific to patent issues.”174

While a preliminary injunction application places a weighty burden on a court’s limited resources, it also presents opportunities for prioritizing case management. Aggressive use of expedited discovery strategies enhances these opportunities. Effectively managing the parties’ expedited discovery demands can put the court in a good position to promote early settlement, summary judgment through revelation of case-dispositive issues, and possibly a consolidated trial under FRCP 65(a)(2).

10.6.7.1 Preliminary injunction

To evaluate a preliminary injunction application, the court uses the traditional four-factor test: the court weighs the applicant’s likelihood of success on the merits, the likelihood of irreparable harm to the applicant, the balance of harm between the parties, and the public interest.175 This standard is essentially the same as that for a permanent injunction, except that the applicant must prove a likelihood of success on the merits rather than actual success.176

After the Supreme Court’s eBay decision, patent owners who demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits no longer enjoy a presumption of irreparable injury if the preliminary injunction is not granted.177 Nonetheless, even though the usual economic consequences of competition – price and market erosion – would likely be calculable and thus “reparable” through a damages award, courts might still conclude that a preliminary injunction is warranted.178

The grant or denial of a preliminary injunction is within the sound discretion of the district court.179 Abuse of discretion in granting or denying a preliminary injunction requires a “showing that the court made a clear error of judgment in weighing relevant factors or exercised its discretion based upon an error of law or clearly erroneous factual findings.”180 The trial court must provide sufficient factual findings to enable a meaningful review of the merits of its order. This requirement does not, however, extend to the denial of a preliminary injunction, which may be based on a party’s failure to make a showing on any one of the four factors, particularly the first two – likelihood of success on the merits and of irreparable harm.

10.6.7.1.1 Discovery

Discovery relating to a preliminary injunction application can touch on nearly every substantive issue in a patent case. Claim construction is usually required, which may in turn require expert discovery if certain terms have special meaning in the art. The plaintiff may require fact and expert testimony as to the defendant’s products, including their development, structure, and operation. The plaintiff’s irreparable harm allegations may require fact and expert discovery as to market conditions and the defendant’s financial condition. The defendant’s invalidity and unenforceability allegations may require discovery into the prosecution of the plaintiff’s patents (especially where the defendant asserts inequitable conduct) and sales by the plaintiff of products covered by the patent (as relevant to a potential on-sale bar argument). The defendant might also seek financial data relevant to the amount of bond necessary should a TRO or preliminary injunction issue.

The initial challenge for a court confronting a preliminary injunction application in a patent case is balancing (1) the need to resolve the application based on a reasonably full record against (2) the twin considerations that (a) a preliminary injunction proceeding needs to be resolved expeditiously, and (b) the parties need to conduct their business in the interim. Where a preliminary injunction application is filed prior to the initiation of discovery, the court can order expedited discovery upon motion or stipulation. Because much of the business information in a patent case is highly confidential, it will likely be necessary for the court to enter a protective order before preliminary injunction discovery can proceed (see Section 10.6.12). In view of these considerations, courts should consider strictly limiting the number of patent claims and prior art references that may be asserted, the number of claim terms that will be construed, the number of depositions that may be taken, the number and nature of document requests, and the issues to be considered.

10.6.7.1.2 Hearing or trial

A court has considerable discretion as to the handling of a hearing for a TRO or preliminary injunction application. FRCP 65 is not explicit about whether the court must have a hearing to consider a preliminary injunction. Given the complexity of patent TRO and preliminary injunction applications, however, courts generally hear arguments. Evidence received on a preliminary injunction motion that would be admissible at trial “becomes part of the trial record and need not be repeated at trial.”181

Since the bulk of the substance of a patent case will be in play in deciding a preliminary injunction, one or more issues may be ripe for final disposition, even at this early stage. For example, a defendant might argue that its product is noninfringing because it is clear that a particular claim element is not in its revised product and that the plaintiff is using patent litigation as a tactic to disrupt or destroy the defendant’s business. In such a case, FRCP 65 presents the court and the litigation “victim” with an opportunity to resolve the issue efficiently in the form of an early trial on the merits, through consolidation with the preliminary injunction hearing.182 A district court may order advancement of trial and consolidation with a preliminary injunction hearing on its own motion.183 Of course, the decision to do so must be tempered by due process considerations.

10.6.7.1.3 Bond

As a result of the potential hardship of a preliminary relief on a defendant, FRCP 65(c) requires the patentee to post a security bond “in such sum as the court deems proper, for the payment of such costs and damages as may be incurred or suffered by any party who is found to have been wrongfully enjoined or restrained.” Because the amount of the security bond is a procedural issue not unique to patent law, the amount is determined according to the law of the district court’s regional circuit. The amount of a bond rests within the sound discretion of a trial court.

10.6.7.1.4 Order

FRCP 65(d)(1)(A) requires that the court address the factors considered in granting or denying the injunction. It must also specifically describe the infringing actions enjoined with reference to particular products.184 An order granting an injunction must explain how the court assessed the four factors, providing the court’s reasoning and conclusion. The order should also address the technology at issue as well as the scope of the injunction and the amount of the bond. Depending on the facts of the case, the court may also need to address the persons bound by the order. Denial of an injunction may be based on a finding that the movant has failed to demonstrate the likelihood of success on the merits or of irreparable harm.

10.6.7.1.5 Appellate review

A district court’s decision on a motion for preliminary injunction is usually immediately appealable, whether it has decided to grant or deny the injunction.185 “A decision to grant or deny a preliminary injunction pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 283 is within the sound discretion of the district court,” reviewed for abuse of discretion.186 “[A] decision granting a preliminary injunction will be overturned on appeal only if it is established ‘that the court made a clear error of judgment in weighing relevant factors or exercised its discretion based upon an error of law or clearly erroneous factual findings.”’187 However, to the extent a district court’s decision is based upon an issue of law, that issue is reviewed de novo.188

Instead of appealing, a party may seek a writ of mandamus from the Federal Circuit ordering imposition or dissolution of a preliminary injunction:

The remedy of mandamus is available only in extraordinary situations to correct a clear abuse of discretion or usurpation of judicial power. A party seeking a writ bears the burden of proving that it has no other means of attaining the relief desired, and that the right to issuance of the writ is clear and indisputable.189

Accordingly, a party dissatisfied with the outcome of a motion for preliminary injunction should first seek to stay the result and file a notice of appeal.190

A party subjected to a preliminary injunction may ask the district court to stay the injunction pending appeal: “While an appeal is pending […] from an order […] that grants, dissolves or denies an injunction, the court may suspend, [or] modify” the injunction.191 Whether to issue a stay of enforcement of a preliminary injunction is within the sound discretion of the district court.192

10.6.7.2 Temporary restraining order

A TRO “is available under [FRCP] 65 to a [patent] litigant facing a threat of irreparable harm before a preliminary injunction hearing can be held.”193 Courts assess the same four factors as for a preliminary injunction in evaluating an ex parte TRO application.

The Supreme Court has explained that “[e]x parte temporary restraining orders are no doubt necessary in certain circumstances, but under federal law they should be restricted to serving their underlying purpose of preserving the status quo and preventing irreparable harm just so long as is necessary to hold a hearing, and no longer.”194 Consequently, TROs are exceedingly rare in patent cases. Entering a TRO enjoining the practice of a given technology can have extreme consequences, including the complete shutdown of a competitor’s business. Further, the factual and legal complexity of patent cases makes it difficult – if not impossible – for a court to make the sort of hair-trigger decisions necessary to grant a TRO application.

While a preliminary injunction may be issued only on notice to the adverse party, a TRO may issue without such notice.195 Nonetheless, where an adverse party has adequate notice of an application for a TRO such that a meaningful adversarial hearing on the issues may be held, the court may treat an application for TRO as a motion for a preliminary injunction. Courts have discretion to handle the hearing, scheduling, and expedited discovery associated with TRO applications in a manner that best suits the circumstances of the case. The court may grant or deny the ex parte application without a hearing. Alternatively, the court may decline to rule on the TRO application until the adverse party has had an opportunity to respond.

A decision to grant or deny a TRO is not usually appealable.196

10.6.8 Discovery

The FRCP provide the overarching framework for pre-trial discovery. These rules authorize broad and extensive pre-trial discovery in civil cases.197 The goal of discovery is to enable the parties to obtain full knowledge of the critical facts and issues bearing on the litigation. By reducing asymmetric information, discovery ideally reduces the range of dispute and facilitates settlement.

The breadth of U.S. civil discovery, in conjunction with the wide range of claims and defenses, high stakes, trade secret sensitivity, and extensive use of electronic record-keeping by technology companies, makes discovery in patent cases especially complex. As a result, discovery can become a strategic battlefield, with better-skilled and -financed parties able to use discovery maneuvers to influence the litigation process. Thus, district judges are often called upon to supervise and balance the discovery process.

Discovery typically commences after the complaint has been filed and the parties have met and conferred. FRCP 26(f) requires the parties to confer as soon as practicable – and, in any event, at least 21 days before a Rule 16 scheduling conference. Due to the fact that many parties and counsel in patent litigation are repeat players, and patent cases are typically filed in a limited set of districts, many aspects of pre-trial patent discovery have been routinized, at least in the early stages of litigation. As noted in Section 10.6.6.1, many district courts and district judges have augmented those rules with PLRs and standing orders that provide detailed disclosure timetables.

FRCP 26(b) provides that, unless otherwise limited by court order:

[p]arties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case, considering the importance of the issues at stake in the action, the amount in controversy, the parties’ relative access to relevant information, the parties’ resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit. Information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible in evidence to be discoverable.

The “proportionality” requirement aims to focus courts and litigants on the expected contribution of discovery to the resolution of the case. This requirement provides district judges with a framework for moderating the extent and costs of discovery based on the nature and scope of the case, the amount of any damages sought and how the case compares to other patent cases.

10.6.8.1 Initial disclosures

Although FRCP 26(a)(1) requires early disclosure of “all documents, electronically stored information, and tangible things that the disclosing party has in its possession, custody, or control and may use to support its claims or defenses,” and “a computation of each category of damages claimed,” a patentee will rarely have access to this information in advance of discovery. Patent damages are based on profits lost by the patentee or, at a minimum, the reasonable royalty that the infringer would have paid to license the patented technology, both of which depend on the sales and offers made by the accused infringer. Thus, much of the evidence as to the patentee’s damages resides in the hands of the accused infringer. Accordingly, initial disclosures as to damages typically only describe the types of damages sought (rather than providing a rough computation of the amount of damages sought) and necessarily defer disclosure of documents and other evidence to a date after discovery has been completed.

10.6.8.2 Document production

Reflecting the broad scope of activities relevant to patent cases, it is common for litigants to propound 100 or more document requests. Document requests typically reach into nearly every facet of a party’s business, including product research and development, customer service and support, sales, marketing, accounting, and legal affairs. The documents must be collected in hard copy from custodians in nearly every department and in electronic form from both the company’s active computer files and all readily accessible archives.

In addition, patent litigation often requires the production of technical information that is highly sensitive and difficult to reproduce for production. Some technical information, such as semiconductor schematics, can only be reviewed in native format using proprietary software that is itself valuable and sensitive. Such information may need to be reviewed on-site on the producing parties’ computers. Computer source code is also highly sensitive and may need to be reviewed in native format. Often, it is produced on a stand-alone computer, unconnected to the internet and in a secure location, and with limitations imposed on the number of pages that may be printed.

Financial information related to damages is also viewed as highly sensitive and can be difficult to produce. Often, in lieu of the underlying financial documents (such as numerous invoices), companies produce reports from their financial databases. They must agree on which categories of information will be produced from these databases or come to terms with the fact that some categories of information cannot be generated by such systems.

Third-party confidential documents, such as patent licenses, are also usually relevant to the damages case, and third-party technical documents can be relevant to the liability case (e.g., if a third party makes the accused chip). The production of these documents often requires permission from third parties, the negotiation of protective orders, or even compulsory process and motions practice.

Document requests in patent cases usually generate multiple motions to compel, motions for protective orders or both. Courts can facilitate more effective document collection and production processes by:

-

reviewing the parties’ electronic discovery plan at the case management conference, as required by FRCP 26;

-

requiring the parties to meet and confer to narrow document requests and to document their efforts in any motion to compel;

-

requiring the parties to file a letter brief seeking permission to file a motion to compel or requiring a pre-motion telephonic conference with the Court, a magistrate or a special master prior to the filing of a motion to compel; and

-

placing a limitation on the number of document requests permitted per side.

10.6.8.3 Interrogatories

FRCP 33(a) has a default limit of 25 interrogatories per party. In their joint case management statement, parties often make a joint request for additional interrogatories. These requests are typically granted because the scope of subject matter in patent litigation is quite broad. Because patent litigation often includes multiple plaintiffs and defendants, however, courts should consider imposing an interrogatory limit per side, rather than per party.

10.6.8.4 Depositions

FRCP 30(a)(2)(A) limits to 10 the number of depositions that may be taken by a party without leave of court. As a result of the breadth of discovery in patent cases, and in spite of the more extensive mandatory disclosure requirements imposed by PLRs, litigants often seek to take in excess of 20 depositions to develop their case, and may legitimately need more than the presumptive 10 depositions. The court should strongly encourage parties to reach mutual agreement in their Rule 26(f) proposed discovery plan regarding the number of depositions or cumulative hours that will be allowed without court order. Absent agreement, a limit should be set to promote the parties’ efficient use of the depositions. A limit of 15 to 20 depositions per side, or about 100 hours, typically provides parties with plenty of opportunity to cover the major issues in a case. Many judges set significantly lower presumptive limits (e.g., 40 hours per side), allowing the parties to petition for more time where justified. The most common practice is to apply these limits to fact discovery, since expert depositions tend to be self-regulating and do not involve inconvenience to the parties themselves.

FRCP 30(d)(1) imposes a one-day (7 hour) limitation on the deposition of fact deponents that should presumptively apply in the absence of a showing of a real need for more time (e.g., if an inventor also has a role in the business). The 30(b)(6) depositions of parties’ organizational officers in patent litigation are, however, often critical to the case. Typically, these depositions can encompass highly technical or detailed information spanning the course of years or even decades. It is often effective to allow 30(b)(6) depositions to continue for more than a single day. However, to prevent runaway 30(b)(6) depositions, the court can also require that each day of a 30(b)(6) deposition counts as a separate deposition for the purposes of the per-side deposition limit. Alternatively, a limit on the total number of deposition hours also helps avoid disputes over how many “depositions” a 30(b)(6) deposition constitutes, when it encompasses more than one topic.

10.6.8.5 Electronic records

A significant portion of discovery in patent litigation is electronic discovery. Although electronic discovery in patent litigation presents similar issues as electronic discovery in other complex litigation, certain challenges arise more frequently in patent cases.

Pursuant to FRCP 26(f)(2), the parties must “discuss any issues about preserving discoverable information; and develop a proposed discovery plan.” The discovery plan produced under Rule 26 must address “any issues about disclosure or discovery of electronically stored information, including the form or forms in which it should be produced.”198 Additionally, each party’s initial disclosures under Rule 26(a) must identify any electronically stored information (ESI) that it intends to use to support its case.

The nature of ESI is such that some types of documents are more accessible than others, ranging from active, online data to nearline data, offline storage and archives, backup tapes, and erased, fragmented, or damaged data.199 Inasmuch as the last two categories contain “inaccessible” data, classification of data can be important in cost-shifting analysis. Under the federal rules, ESI is presumptively not discoverable if it comes from a source that is “not reasonably accessible because of undue burden or cost.” To raise the presumption, the responding party to a discovery request must identify the sources that are “not reasonably accessible” that it will not search or produce. In response, the requesting party may challenge the designation by moving to compel, whereupon the burden shifts to the responding party to show that the information is not reasonably accessible. The court may then hold that the information is not reasonably accessible and so is presumptively not discoverable. Even if the requesting party shows “good cause” to obtain production, the court may specify conditions on the production, such as cost-shifting.

Although there is much wisdom in this effort to reduce the costs of e-discovery, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and greater experience in managing the scope of electronic discovery will likely result in further evolution and explication of the various guidelines. For example, in many cases, the most expensive ESI to collect is not email, which is often stored on relatively accessible central servers, but rather the contents of the computer hard drives of individual users, which must be individually copied or “imaged” to collect and produce the users’ working documents. Parties often look to their FRCP 26(a) initial disclosures to determine whose computers should be imaged.

10.6.8.6 Management of discovery disputes

District judges vary in how they deal with discovery disputes. Some judges refer discovery management to magistrate judges so as to reduce their need to deal with what can be frequent skirmishes. By contrast, some judges find that handling discovery disputes keeps them abreast of developments in the case and enables them to coordinate discovery and scheduling issues. Moreover, there can be an in terrorem effect at work when the district judge hears discovery disputes – litigants may be less likely to raise as many disputes and will likely be more conciliatory if the judge deciding the case has a greater opportunity to assess whether counsel have been unreasonable. Where referral is the common practice, experienced counsel soon learn the tendencies of the magistrate judges on particular issues, resulting in fewer motions. If this does not happen, or if the case otherwise appears likely to generate a disproportionate level of discovery controversy, courts can require the parties to engage a special master under FRCP 53. When the special master possesses substantial experience with patent litigation, the resulting process, although sometimes costly, can be substantially more efficient and effective.

10.6.9 Summary proceedings

District courts “shall grant summary judgment if the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.”200 Effective utilization of the summary judgment process is especially important in patent cases because such cases present so many complex issues. Summary judgment can play a critical role in resolving the case or narrowing or simplifying the issues, thereby promoting settlement or simplifying the trial. Conversely, the summary judgment process in a patent case can put a significant burden on the court, particularly if the parties file numerous, voluminous motions.

Effective management of the summary judgment process in patent cases requires an understanding of the types of issues that drive most patent cases, how they typically unfold over the life of a case, and if and when they are amenable for summary adjudication. The timing of summary judgment motions can be critical: if summary judgment proceedings are held too early for a given case, questions of fact that would have been resolved at a later stage preclude summary judgment. However, deferring summary judgment too long risks wasting the time and resources of the parties and the court on issues that limited discovery could have resolved.

10.6.9.1 Distinguishing questions of law from questions of fact

FRCP 56(a) authorizes summary adjudication of issues of law, where there is no disputed question of fact. That is, a court may only entertain summary judgment of pure questions of law, mixed questions of law and fact on which there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact, and undisputed questions of fact. These distinctions are especially subtle in patent litigation, reflecting the complex interplay of fact and law. Furthermore, even though the ultimate claim construction determination is a question of law potentially based on subsidiary questions of fact, the subsidiary facts are within the province of the court, thereby expanding the range of issues that can be resolved on summary judgment. The common issues in most patent litigation – novelty, nonobviousness, and adequacy of written description – involve factual questions or are questions of law based on underlying questions of fact.

The issues least amenable to summary judgment are typically those that have the following characteristics: (1) require a high burden of proof, (2) are questions of fact, (3) are broad issues requiring the movant to establish a wide range of facts, and (4) involve subjects about which the underlying facts are typically disputed. One of the most vexing questions in U.S. patent law today is the extent to which patent eligibility can be resolved at the motion to dismiss or summary judgment stage of litigation.201

10.6.9.2 Multi-track approach

The information necessary for assessing summary judgment emerges during discovery, case management conferences, claim construction, and other pre-trial processes. It is useful, therefore, to approach summary judgment case management as a multi-track process: (1) claim construction-related, (2) non-claim construction-related, and (3) off-track. Notwithstanding the caution about diverting judicial resources from claim construction, there may be an issue that arises early in the litigation that does not require claim construction and that can either resolve the entirety of the case or substantially streamline the case.

For example, Section 271(a) of the Patent Act imposes infringement liability on persons who “without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any patented invention, within the United States or imports into the United States any patented invention during the term of the patent.” Whether an allegedly infringing act occurred within, or outside of, the United States is a question of law, whereas whether an act occurring within the United States is sufficient to constitute a sale, offer to sell, use, manufacture, or importation is a question of fact. Typically, the parties agree that a certain set of events took place in certain locations, but dispute the conclusions to be drawn from these events as they relate to infringement. As a result, both questions – the locus and the characterization of the acts – are often amenable to summary judgment. Such a decision does not implicate claim construction and, therefore, might usefully be addressed early in the litigation process.

10.6.9.3 The summary judgment process and hearing

Notwithstanding the usefulness of summary adjudication in streamlining and resolving some patent cases, the potential exists for parties to inundate the court with summary judgment motions that can disrupt orderly and efficient case management. Consequently, courts have developed a variety of case management techniques for streamlining the summary judgment process, including (1) pre-screening – requiring the parties to file concise letter briefs requesting permission to file summary judgment followed by a telephone hearing to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed motion(s); (2) quantitative limitations, such as restricting the number of summary judgment motions and the total number of briefing pages, or consolidating motions into a single briefing; and (3) multiple rounds of summary judgment motions. These approaches are not mutually exclusive, and each has advantages and disadvantages based on the nature of the case and contentiousness of the parties. The first approach enables the judge to screen cases more efficiently: competent counsel can usually convey enough information to the court in two to three pages and five minutes of oral argument to enable the court to evaluate whether the substance of a proposed motion justifies a full briefing. The second approach motivates the parties to prioritize their motions. The third approach promotes efficient staging.

Most judges opt for an oral hearing on summary judgment motions. There is rarely any need for live testimony because the court cannot resolve factual disputes through summary adjudication. Live testimony can, however, be useful where declarations submitted by the parties do not squarely address each other and create the perception of a question of material fact when, in reality, one might not exist. The court might want to have a technology tutorial focused on the particular issues presented by the summary judgment motion(s), especially if the claim construction technology tutorial did not cover these areas. The length of time needed for a summary judgment motion varies widely depending on the court’s preferences and the scope and nature of the issues at stake.

10.6.10 Evidence

Patent cases are characterized by motions – often many – directed at excluding or limiting the use of evidence, including motions attacking expert opinions.202 It is common practice to resolve such issues substantially in advance of trial so that the parties return with their presentations appropriately honed in accordance with the court’s limiting orders.

10.6.10.1 Technical and economic expert witnesses

Daubert sets forth a nonexclusive checklist for trial courts to use in assessing the reliability of scientific expert testimony: (1) whether the expert’s technique or theory can be or has been tested – that is, whether the expert’s theory can be challenged in some objective sense, or whether it is instead simply a subjective, conclusory approach that cannot reasonably be assessed for reliability; (2) whether the technique or theory has been subject to peer review and publication; (3) the known or potential rate of error of the technique or theory when applied; (4) the existence and maintenance of standards and controls; and (5) whether the technique or theory has been generally accepted in the scientific community.

Apart from the subject matter distinction between scientific or technical and economic (damages) experts, patent cases involve two distinct types of expert testimony. The first, common to most other types of litigation, involves applying an accepted technical, scientific, or economic methodology to facts established during the trial to reach conclusions about factual issues. An expert might testify, for example, about the results of their analysis to determine the chemical composition of the accused product. Because this type of testimony is directed to an analysis that the expert regularly performs outside of a litigation context, it falls squarely within the FRE 702 and Daubert frameworks. Consequently, it presents few novel issues.

The second type of testimony presents more challenges. In patent cases, an expert is often asked to use their scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge to evaluate a hypothetical legal construct. Examples include:

-

Who is a “person having ordinary skill in the art”?

-

Would a “person having ordinary skill in the art” believe at the time of alleged infringement that differences between the patent claim and the accused product are “insubstantial”?

-

At the time the patent application was originally filed, would a “person having ordinary skill in the art” have had a motivation to combine known ideas to create the claimed invention?

-

What royalty rate would the patentee and the infringer have agreed upon had they participated in a negotiation at the time of first infringement knowing that the patent was valid and infringed?

The court’s gatekeeping function is more nuanced in these areas. Because it reflects a hypothetical legal construct, it necessarily departs from the type of generally accepted, peer-reviewed methodology contemplated by FRE 702 and Daubert.

Courts have wide discretion to determine the process and timing for resolving the admissibility of expert testimony. Although they can address Daubert challenges in conjunction with summary judgment or motions in limine, these approaches tend to give short shrift to the Daubert inquiry. Thus, many judges consider the admissibility of expert testimony through a specific Daubert briefing or hearing schedule for Daubert motions in the case management order.

The optimal time for scheduling such motions is after experts are deposed on their reports, but well before the pre-trial conference. Timing the briefing and hearing this way will ensure that a full record is available, but also give the court adequate time to consider the merits of each challenge. In addition, early consideration of Daubert challenges prevents the risk of a party being denied any expert at trial, which in some circumstances can be a harsh sanction for a correctable error. For example, a common Daubert challenge to a damages expert is based on an alleged incorrect date for the hypothetical negotiation for the determination of a reasonable royalty. Determining this date can be challenging: not only because it depends on technical information related to infringement that is usually beyond the purview of damages experts, but also because the trial court’s summary judgment rulings can affect that date. In this circumstance, even if a damages expert’s methodology is adequate, the factual basis for the analysis may be incorrect as a matter of law. Once informed by the court’s summary judgment rulings, the expert can revise their analysis to include the correct information – so if the question is raised through an in limine motion on the eve of trial, it would be unjust to grant the motion and strike the expert. Consequently, many courts hear Daubert challenges at the same time as, but separate from, summary judgment motions.

10.6.10.2 Patent law expert witnesses

Parties sometimes propose presenting expert testimony regarding patent law, procedures of the USPTO, patent terminology, prosecution history, or specific substantive (e.g., anticipation) and procedural (e.g., what a “reasonable patent examiner” would find material) issues through a patent attorney or former USPTO employee. In support of this testimony, parties often point out that the evidence rules specifically permit opinions on ultimate issues203 and the presentation of testimony without first specifying underlying facts or data.204

Testimony on issues of law by a patent law expert – as contrasted with a general description of how the patent process works – is usually inadmissible. Just as in any other field, it is exclusively for the court, not an expert, to instruct the jury regarding the underlying law. Conversely, testimony regarding the procedures and terminology used in patents and file histories, on the other hand, is often allowed. In many cases, however, this testimony might be redundant in light of a preliminary jury instruction explaining those procedures. Because a jury instruction is likely to be more neutral, it will usually be a preferable means of providing this information to the jury. A jury instruction, however, may lack sufficient specificity to explain a USPTO procedural event relevant in a particular case, and in that circumstance, expert testimony is more likely to be appropriate and helpful to the jury.

The admissibility of proffered patent expert testimony on ultimate issues will often depend on whether the expert is doing anything more than applying patent law to a presumed set of facts, essentially making the jury’s determination. This is particularly true if the proffered patent expert has no relevant technical expertise. Thus, a patent expert’s opinion regarding matters such as infringement, obviousness, and anticipation based on technical conclusions that are assumed or provided by a different expert is usually improper. Similarly, testimony applying patent law to issues intertwined with patent procedure, but dependent on technical conclusions supplied by others, such as the appropriate priority date of a claim in a continuation application, is usually inappropriate. Conversely, if the patent expert also has relevant technical expertise, she should be equally able to provide expert testimony within that expertise as would be any nonlegal expert with similar technical expertise.

In trials to the court, when there is no concern regarding jurors’ overreliance on expert testimony, courts more freely admit the testimony of patent law experts. This includes, for example, testimony regarding whether a reasonable patent examiner would deem particular prior art or statements important in an inequitable conduct determination. Courts have found such testimony helpful and allowed it.205

Testimony is sometimes offered regarding the abilities of patent examiners, their workloads, time spent on applications, or similar matters. This testimony, which is meant to bolster or undermine the statutory presumption of validity, is improper.206 The deference the jury should give to the actions of the patent examiners is an issue of law like any other.

10.6.10.3 Inventor and technical employee witnesses

Inventors and other technical employee witnesses often testify at trial regarding the invention and other technical matters. These witnesses frequently would qualify as experts and, if properly disclosed as testifying experts, appropriately may provide expert testimony. Because their duties likely do not “regularly involve giving expert testimony,” no expert report is required by such employees absent special order; however, ordering such a report usually is appropriate and is a provision that might be included in the case management conference order.207

If inventors and other technical employees are not disclosed as experts, difficult line-drawing questions can arise regarding their testimony. For example, when an inventor or co-employee testifies regarding the invention to a jury, it is usually necessary to accompany the testimony regarding historical acts with an explanation of the technology involved. These explanations are sometimes challenged as undisclosed expert testimony. Other testimony that often draws a challenge is inventor or employee testimony regarding the nature of the prior art at the time the invention was made. While testimony about the invention and prior art may be highly technical, it may involve the description of historical facts without the expression of opinion. In that event, the non-opinion testimony is proper without expert disclosure. Such testimony, however, is sometimes employed in an attempt to introduce undisclosed opinion into evidence. Courts have discretion to admit into evidence demonstratives that summarize admissible evidence.208

10.6.10.4 Motions in limine