Chapter 12 Spain

Authors: Ángel Galgo Peco, Alberto Arribas Hernández, Enrique García García and Luis Rodríguez Vega

12.1 Overview of the patent system

12.1.1 Evolution and current state of the patent system

The origins of the current patent system in Spain date back to Law No. 11/1986 of March 20, 1986, on Patents (LP-1986).1 In its day, that Law represented a complete overhaul of an obsolete patent regime based on principles established in the early 20th century. That reform took place in the context of Spain entering what was then called the European Economic Community. The negotiations for its entry included discussions on the provisions of and accession to the Convention on the Grant of European Patents, of October 5, 1973, or “European Patent Convention” (EPC).2 LP-1986 incorporated provisions from that Convention and from the Luxembourg Convention on the Community Patent, of December 15, 1975.

After entering into force, LP-1986 underwent various partial revisions to adapt it to new regulatory developments within the European Union and internationally. A subsequent, more comprehensive revision resulted in Law No. 24/2015 of July 24, 2015, on Patents (LP-2015),3 which entered into force on April 1, 2017, and remains in effect today.

LP-2015 introduced some major innovations relative to LP-1986, and most significantly the following:

-

The possibility of patenting previously known substances or compositions was explicitly recognized for use as medicines or new therapeutic applications.

-

In addition to patents and utility models, explicit provision was made for industrial property rights in the form of supplementary protection certificates, to cover medicinal and plant protection products.

-

Substantive examination (of novelty and inventive step), formerly optional for applicants, was established as the only procedure required for the granting of patents.

-

A system of opposition was established for patents previously granted, under which anyone may oppose the granting of a patent within six months after publication of the grant, on the following grounds: (i) failure to meet patentability requirements; (ii) lack of sufficient clarity in the description; and (iii) patent protection beyond that specified in the application. Such proceedings are brought before the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (SPTO), and can result in invalidation or modification of the patent.4

-

The patent owner’s ability to obtain the amendment of their patent from the SPTO – and from courts in cases where civil litigation has been brought to invalidate a patent – was explicitly recognized.

-

The regulations with regard to compulsory licenses were restructured and simplified.

-

Provision was made for interested parties to settle patent disputes through mediation or arbitration.

With regard to patent-granting procedures, distinctions are drawn between three types of patents in Spain:

-

patents obtained based on applications to the SPTO (after following a grant procedure established in the 2015 law);

-

patents sought by means of an international application, subject to the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT)5 (in force in Spain as of November 19, 1989); and

-

European patents validated in Spain (European patents are granted by the European Patent Office (EPO) in accordance with the EPC and produce effects in contracting States designated by the patent owner).

Patents granted by the SPTO based on an international application are equal, in terms of their effects and validity, to patents granted based on national applications.6

In the same way, European patents designating Spain produce the same effects and are subject to the same regime as Spanish patents.7 In this case, however, the patent owners must provide Spanish translations of their European patents, as granted,8 within three months after their publication.

As mentioned, LP-2015 continues to provide for utility models. Legislators cited the large number of applications for that modality and the high percentage of Spanish national applicants as justification for this decision. The newer law also continues to treat utility models as a sui generis form of IP, not a “simplified patent”. Significant changes have been made, however, to the earlier regulations. The current regime can thus be characterized as follows:

-

State of the art, which is the benchmark used to assess novelty and inventive step, is understood in the same way for utility models as for patents, as referring to everything that was available to the public, in Spain or elsewhere, prior to the patent application filing date. The essential difference is that the level of inventiveness required for utility models remains lower than that for patents.

-

The scope of protection for utility models is quite broad, excluding only inventions consisting of procedures and those relating to biological materials and pharmaceutical substances and compositions – understood as those used as medicines for humans or animals.

-

The grant procedure for utility models does not entail a substantive examination.

-

However, for actions to be brought against infringement, a report must be obtained on the state of the art for the subject matter of the industrial model concerned.

-

The protection afforded for utility models entitles their owners to the same rights as those enjoyed by patent owners. On the other hand, the duration of protection for utility models is only 10 years, without the possibility of extension, compared to 20 years for patents.

Supplementary protection certificates for medicines and plant protection products are addressed in Section 12.13.1 below.

As a final point for this Section, it should be noted that Spain has not joined yet the system of European patents with unitary effect,9 which entered into force on June 1, 2023.

12.1.2 Patent application trends

After LP-2015 went into force, in 2017, the number of applications for utility models decreased. One factor that may explain this decline was that infringement actions for utility models were then conditioned on owners obtaining a report on the state of the art, which had not been required before.

In the case of patents, studies showed that while fewer applications were being submitted and granted for national patents, the number of those for international patents received from Spanish applicants – as well as for European patents ultimately validated in Spain – increased.

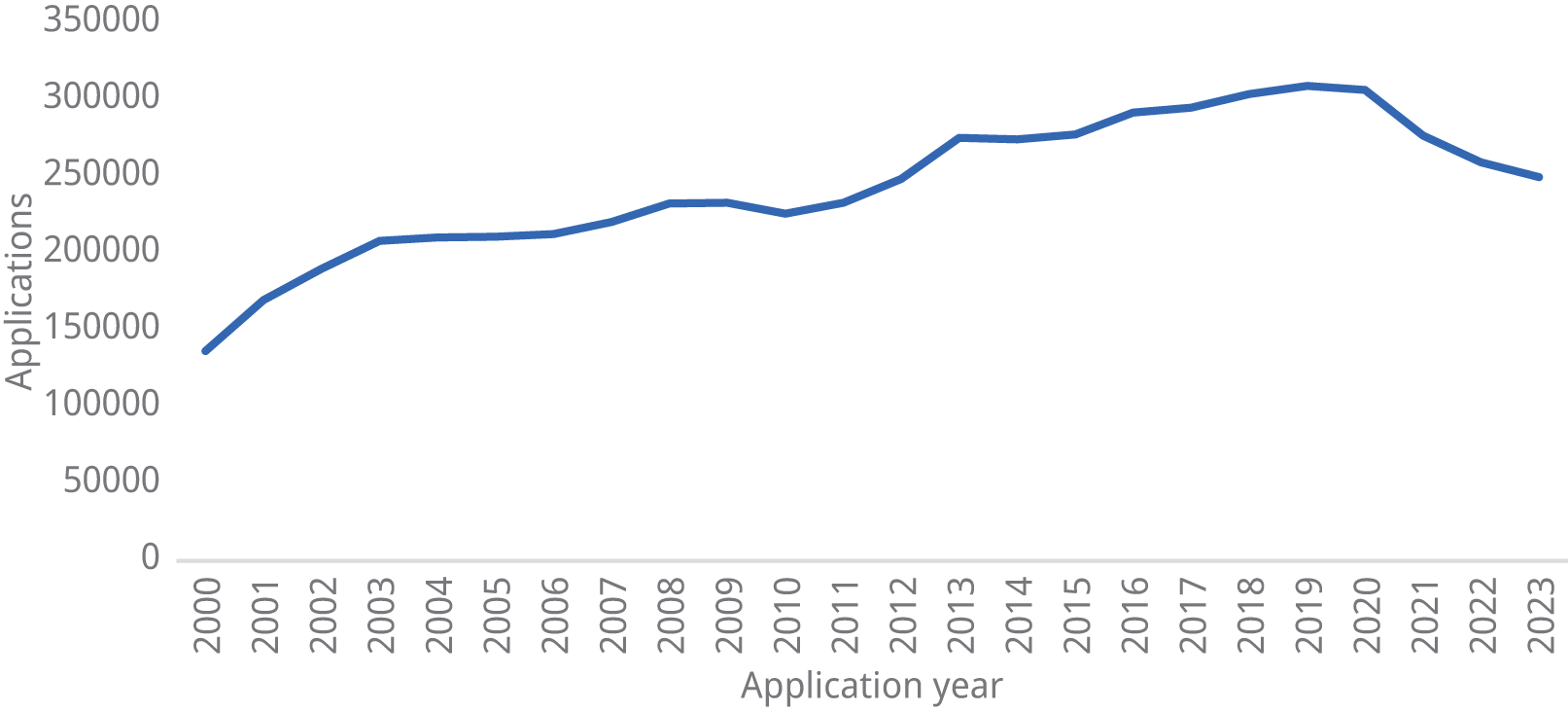

Figure 12.1 shows the total number of patent applications (direct, PCT national phase entry and European patent ES designation) filed in Spain from 2000 to 2023.

Figure 12.1 Patent applications filed in Spain, 2000-2023

Source: WIPO IP Statistics Data Center, available at www3.wipo.int/ipstats/index.htm?tab=patent and EPOPATSTAT, available at www.epo.org/searching-for-patents/business/patstat.html

12.2 Spanish Patent and Trademark Office and administrative review procedures

12.2.1 Spanish Patent and Trademark Office

The SPTO is responsible for the administration of industrial property. This includes administrative activities relating to recognition and registration of protection for the various forms of industrial property (with the exception of plant varieties); processing and decision-making for applications and related procedures (granting, limiting and invalidating industrial property titles, among others); record-keeping and publicity.

The SPTO is an autonomous agency attached to the Ministry of Industry and Tourism with its own legal personality and capacity to operate in pursuance of its mandate.

12.2.2 Administrative review procedures

Acts and decisions taken by SPTO bodies in proceedings of various kinds include the handling of administrative appeals, which the SPTO itself both processes and resolves. Final SPTO decisions mark the exhaustion of administrative remedies and are then subject to judicial review.

Judicial appeals against all kinds of final SPTO decisions have traditionally been handled by administrative courts. That changed in 2022, when legislation assigned jurisdiction to specialized civil courts for appeals against SPTO industrial property decisions when those decisions marked the exhaustion of administrative remedies (see Section 12.3.1).

Since the entry into force of LP-2015, the interplay between proceedings brought before the SPTO and those handled by courts, apart from that described above, has raised a point of particular interest: the possibility allowed for patent owners10 to amend their patents through recourse either to the SPTO (limitation procedure) or to the courts, in the context of civil action seeking invalidation of the patent (see Section 12.4). Since this two-track framework can result in conflicting situations, the law provides for ways to coordinate procedures. The law stipulates that courts must notify the SPTO when limitation of a patent has been sought in the context of invalidation proceedings, and the SPTO must in turn enter that fact into the Patent Registry. Once the court has made its final ruling on the limitation request it must then notify the SPTO accordingly, also for entry in the Patent Registry. It is stipulated further that when proceedings for the invalidation of a patent are pending before a court, the acceptability of requests for limitation of the patent is subject to that court’s authorization. Lastly, if, during the course of invalidation proceedings before a court, the patent should be amended by the SPTO pursuant to a request made before the start of court proceedings, the owner may request that those proceedings be based on the patent as so amended.

Similar issues arise from the interplay between proceedings before the EPO and national courts concerning the validity of European patents previously validated in Spain. As mentioned earlier, European patents are granted through centralized procedures before the EPO and then replicated as multiple national patents in countries designated by the patent owner. Opposition procedures are also centralized through the EPO, which are conducted before the Opposition Divisions, whose decisions are reviewable in the last resort by the Boards of Appeal. The European process for limiting patents works in a similar fashion.

This can result in situations where the same question is raised about the same European patent before the EPO (in the context of opposition or limitation proceedings) and before national courts (in the context of invalidation proceedings), the patent having been previously validated in the contracting State concerned. The following guidelines then apply:

-

A decision by the national court to invalidate the (previously validated) patent produces effects only in the contracting State concerned.

-

A decision by the EPO to revoke or amend a European patent produces effects in all of the contracting States designated, even if national courts in one or more of those States have previously validated it.

-

The national court decision to invalidate the patent produces effects in the contracting State concerned even if the EPO has decided to maintain its validity, in which case it remains valid in all other contracting States having validated it.

In the event that challenges to the validity of a European patent are brought on parallel tracks, before both the EPO and a national court (in the context of infringement proceedings), it is not uncommon for the national court to find the patent valid and to have been infringed and to order legal remedies pursuant to national law – and then, on the parallel track, for the patent to be revoked by a decision of the EPO.

Since the late 1990s, in order to avoid such situations, EPO bodies have been asked to “accelerate their proceedings.” Various other remedies are also available under the national laws of contracting States. In the case of Spain, however, since national law does not specifically provide for such circumstances, the only solution at present is recourse to the instruments offered by general procedural rules. On this point, the Provincial Court of Madrid11 has considered that when a ruling is to be made, if opposition proceedings are also underway before the EPO, the judicial proceedings should be suspended subject to agreement by the parties. The Provincial Court of Barcelona, on the other hand, has considered under the same circumstances that the court can suspend the proceedings ex officio.12

12.3 Judicial institutions

12.3.1 Judicial administration structure

The Spanish Constitution provides that exercise of the judicial power for all types of trials, judgments and enforcement of judgments rests exclusively with juzgados and tribunales as defined by the laws and in accordance with the rules of competence and procedure set forth therein. The term juzgados refers to courts composed of a single judge. The term tribunales refers to collegial bodies composed of at least three judges.

The judicial function is performed solely by professional judges forming part of the judicial service, which is divided into three categories: Supreme Court Justice, Magistrado (Senior Judge) and Judge. Courts in Spain are composed exclusively of judges with judicial training.

The Spanish Judiciary is governed by the General Council of the Judiciary. This body is recognized as having all of the powers necessary to apply the rules governing the exercise of functions performed by members of the Judiciary, particularly in matters pertaining to appointments, promotions, inspections and disciplinary measures.

The Constitution also establishes principles for the governance of judicial activities. One such principle, jurisdictional unity of the National Judiciary, underlies the organization and functioning of all Spanish courts.

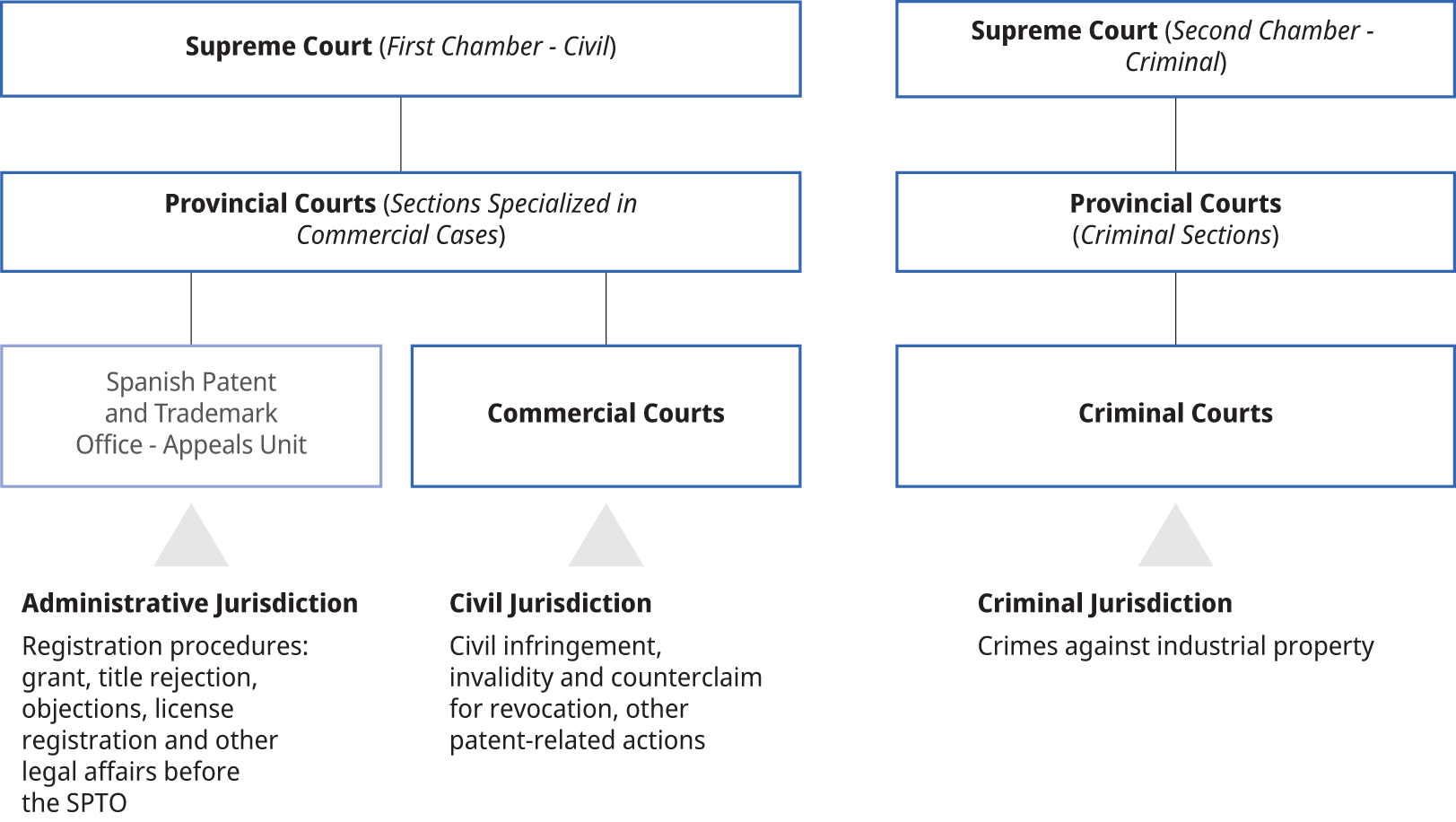

The ordinary courts are classified into four jurisdictional divisions: civil, criminal, administrative and social.13 The Supreme Court, with jurisdiction throughout Spain, is the highest judicial body for all of these divisions, except where constitutional guarantees are concerned, for which that position is occupied by the Constitutional Court.

Within each of these jurisdictional divisions, specialized courts have been created by various legislatively authorized means to deal with specific matters. Such is the case for courts specializing in industrial property cases, which are part of the courts specializing in commercial matters and forming part of the civil jurisdictional division.

The Organic Law on the Judiciary14 provides for the establishment, operation and governance of the courts as well as rules governing the exercise of functions performed by members of the Judiciary, including judges and administrative staff. It also regulates the election, composition, powers and operations of the General Council of the Judiciary and the exercise of functions performed by General Council members.

Figure 12.2 The judicial administration structure in Spain

12.3.2 Courts specialized in industrial property

LP-1986 provided for the possibility of patent-related cases (and by extension other industrial property cases) being considered by certain first instance courts (“juzgados de primera instancia” - traditional denomination of the courts of first instance of the civil jurisdictional division). That possibility, however, never materialized in practice.

The real change took place in 2003, with an amendment to the Organic Law on the Judiciary.15 That amendment established one or more commercial courts in each province, with jurisdiction for each entire province. These new courts were assigned competence to hear cases in the first instance relating to a finite list of subject matters that included industrial property, intellectual property, fair competition and publicity. The reform also established a specialized role for the country’s Provincial Courts (second-instance courts within the civil and criminal jurisdictional divisions): that of hearing appeals against decisions by these new commercial courts. These courts began operating in January 2004.

Current patent law in Spain, LP-2015, after entering into force in 2017, carried this specialization process a step further, assigning competence for civil patent cases to specific commercial courts – those located in the autonomous community seats of the country’s High Courts of Justice – the highest courts in each of the country’s autonomous communities (except for cases subject to Supreme Court jurisdiction). The General Council of the Judiciary would previously have conferred exclusive jurisdiction for such matters to the High Courts themselves.

As a consequence of the resolutions adopted by the General Council of the Judiciary, six commercial courts in Madrid, three in Barcelona and one in Valencia have been assigned jurisdiction for civil proceedings concerning patents. There are also commercial courts for Granada, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, La Coruña and Bilbao.

The “super-specialization” process continued in 2022 for second-instance courts, with another reform of the Organic Law on the Judiciary.16 Under this latest reform, where a Provincial Court has more than one section specialized in commercial cases, the General Council of the Judiciary must distribute competence for specific matters among the sections. Explicit provision was also made for the possibility of creating specialized sections to deal exclusively with intellectual and industrial property, fair competition and publicity.

Only the Provincial Court of Madrid has more than one section specialized in commercial cases. Under the reformed provisions, Section 32 of the Provincial Court of Madrid was assigned sole and exclusive jurisdiction for intellectual and industrial property, fair competition and publicity, the only section so specialized in Spain.

There is no such structured specialization at the Supreme Court level (First Chamber).

Another important change made by the 2022 reform was to assign jurisdiction to Provincial Court sections specialized in commercial cases for appeals against final SPTO rulings on industrial property cases, hitherto subject to administrative jurisdiction.

Courts specializing in commercial cases are composed exclusively of judges with legal rather than technical training.

To ensure that the judges selected for these specialized courts have the necessary knowledge, a selection procedure has been established to qualify successful candidates as “commercial law specialists”. Those so qualified are then given preference when judges are appointed to the specialized commercial courts. Only when there are no commercial law specialists may a non-specialized judge be appointed to these courts.

The selection process consists of exercises to test theoretical knowledge and skill in drafting opinions. Successful candidates are then offered a theoretical-practical training course conducted by the Judicial School of Spain. As an eligibility requirement for participation in this process, judges must have effectively served for at least two years.

Members of the judicial service who are not specialists but do obtain an appointment to a commercial court must participate in specific training activities as determined by the General Council of the Judiciary (an online theoretical course and a theoretical-practical internship with a commercial court).

12.3.3 Relationship between invalidity and infringement proceedings

Within the country’s unitary judicial system, courts competent to hear invalidation cases are the same as those competent for infringement cases, so that a single court can deal with both issues as part of the same proceedings.

It is thus not uncommon for defendants in infringement cases to seek invalidation of an allegedly infringed patent by way of either a defense or counterclaim. In such cases, without prejudice to procedural particularities triggered by invalidation requests (see Section 12.4), the proceedings continue before the same court, which will then rule on both invalidation and infringement as part of the same decision on the merits.

In the event of parallel judicial proceedings, the risk of contradictory rulings is avoided by means of a consolidated process, as provided for in the procedural rules. If such consolidation is not possible, the court hearing infringement proceedings can suspend them until the invalidation proceedings have been concluded.

12.3.4 Judicial training on industrial property

As one of its key functions, the General Council of the Judiciary is responsible for the continuous, in-service training of members of the judicial service, which is provided by the Judicial School. The Continuing Training Service of the Judicial School is charged with ensuring that all members of the judicial service receive high-quality, continuous, individualized and specialized training throughout their careers.

The State Training Plan, developed annually, constitutes the fundamental core of the training activities overseen by the General Council of the Judiciary. It encompasses a wide range of activities, in various formats, covering legal but also related subjects, such as economics and foreign languages. Participation by judges in these activities is voluntary. The Plan includes specific training activities on the subject of industrial property.

The Plan also includes joint training activities with other agencies and entities, including the SPTO.

The Judicial School is part of the European Judicial Training Network, which each year organizes international seminars as well as exchange and study visits to courts in other European Union countries. This includes activities related to industrial property.

12.4 Patent invalidity

The validity of a patent can be impugned on the grounds indicated in Article 102(1) of LP-2015, which reads as follows:

A patent shall be invalidated:

- (a) when it is demonstrated that the subject matter of the patent does not meet one of the requirements contained in Title II of this Law;

- (b) when it does not describe the invention in a sufficiently clear and complete manner for it to be executed by an expert in the subject matter;

- (c) when its subject matter exceeds that contained in the patent application as submitted, or if granted in response to a divisional application or an application based on Article 11, when the subject matter exceeds that contained in the initial application as submitted;

- (d) when the protection conferred by the patent has been expanded after the patent was granted; and

- (e) when, according to Article 10, the owner of the patent did not have the right to obtain it.

12.4.1 Grounds for invalidation

12.4.1.1 The requirements for patentability

The first ground for invalidation is failure to meet any of the requirements for patentability. According to Article 4 of LP-2015 “Inventions that are novel, that involve an inventive step and that are capable of industrial application are patentable in all fields of technology.” Thus, the requirements of patentability are novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability.

Article 5 of LP-2015 also provides for exceptions to patentability, such that a patent can also be impugned, and its subject matter considered unpatentable, for falling under those exceptions.

Patents are most frequently challenged, however, for lacking novelty or an inventive step.

12.4.1.1.1 Novelty

Article 6 of LP-2015, in terms similar to those of Article 54 of the EPC, reads as follows:

An invention shall be considered to be new if it does not form part of the state of the art.

State of the art is defined in Article 6(2) as:

everything made available to the public, in Spain or abroad, by means of a written or oral description, by use, or by any other way, before the date of filing of the patent application.

Article 6(3) goes on to specify the following:

Additionally, the content of Spanish patent or utility model applications, of European patent applications designating Spain, and of international PCT patent applications that have entered the national phase in Spain, as filed, with an earlier filing date than that indicated in the preceding subparagraph and published in Spanish on or after that date, shall be considered as comprised in the state of the art.

The relevant date will be the submission date of the application, unless priority has been claimed for “an original application for a patent, a utility model or a utility certificate in or for any of the States parties to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, done in Paris on March 20, 1883, or of the Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization,” if filed within the previous 12 months. “As a result of the exercise of the right of priority, for the purposes of the provisions set out in Sections 6, 10(3) and 139, the filing date of the patent application shall be deemed to be the filing date of the earlier application whose priority has been rightfully claimed.”17

Assessing the novelty of a patent means comparing each patent claim, interpreted according to the description and drawings provided, against a single state-of-the-art disclosure (document).

A claim is considered to lack novelty when a document or other form of state-of-the-art disclosure, directly and unambiguously (that is, undoubtedly) anticipates each and every element of the claim at issue.

In practice, national courts apply the criteria set out in the Case Law of the EPO Boards of Appeal, summarized in the method described in the Guidelines for Examination and in the Spanish Patent Office Guidelines. The method for assessing novelty consists of three steps:

- 1. identify the technical elements of the invention claimed, with reference to the expert opinions provided by the parties, for comparison with one or more state-of-the-art documents;

- 2. determine whether the document cited by the party challenging the patent forms part of the state of the art; and

- 3. assess whether, at the time of its publication, the document said to anticipate the challenged claim explicitly or implicitly disclosed all of that claim’s elements or steps for a person skilled in the art.

In making this last comparison, the first fundamental rule in assessing novelty is not to combine disclosures from different state-of-the-art documents for comparison with the elements of the challenged claim. Doing so would misrepresent the state of the art: the novelty of the claimed invention may in fact lie in combining different state-of-the-art solutions. These comparisons must therefore be made document by document18 (anticipation by anticipation). Not even different processes covered in the same document should be combined unless that combination is suggested therein. An exception to this first rule is when a document (the main document) refers explicitly to other documents that have also been published to provide more details on a given characteristic.

The technical teachings provided in the document must be considered as a whole, as a person skilled in the art would do. Separate parts of a given document must not be taken arbitrarily out of context to extract technical information that differs from or contradicts, the document’s overall disclosure, considered as a whole. In challenging the novelty of a claim, it is acceptable to combine separate passages (teachings) from a single document, but reasons must be given for concluding that a person skilled in the art would do so.

The third step of this method, in making comparisons between prior disclosures and more recent claims, involves this concept of “a person skilled in the art”, with reference to the subject matter of an invention. This concept is generally understood to refer to the notion of a skilled practitioner in the relevant field of technology aware of what was “common general knowledge” in the art at the relevant date and of the means normally used to perform relevant routine work and experimentation in that field. The special characteristic of this archetypical skilled practitioner (or team of practitioners) is access to all the knowledge that defined the state of the art, and in particular the documents that need to be compared with the invention claimed.

Thus, differences between the invention claimed and what is disclosed in a prior document are assessed by considering what a person skilled in the art, after reading the document, would consider to have been disclosed. Logically, according to Article 335 of Law No. 1/2000 of January 7, 2000, on Civil Procedure (LEC),19 such knowledge must be brought to the court by experts witnesses. The concept of a “person skilled in the art” must not, however, be confused with such witnesses but rather be invoked by the judge, a layperson in this context, after considering the insights provided by expert witnesses to justify the comparison. The function of the expert witness is thus to assist the judge by identifying, reading and correctly assessing documents forming part of the state of the art that are being cited as the basis for challenging the novelty of a claimed invention.

The elements of a patent claim may have been disclosed by an earlier document either explicitly or implicitly.20

Express disclosures: A document which forms part of the state of the art deprives the claimed invention of novelty, if a reading thereof reveals that the claimed elements are obvious, straightforward and unambiguous to a person skilled in the art. It should be noted that the implicit characteristics of all the elements explicitly mentioned in the document are also understood to have been disclosed to the person skilled in the art. One thing that cannot be done, when assessing novelty, is to include well-known equivalents, as such document interpretation is characteristic of the analysis of inventive step.

Subject matter described in a document can only be regarded as having been made available to the public if the information given therein is sufficient to enable the skilled person, at the relevant date of the document and with the general knowledge assumed to be available at that time, to practice that technical teaching. Similarly, a chemical compound, whose name or formula is mentioned in a state-of-the-art document, is not thereby considered as known, unless the information in the document, together with knowledge generally available on the relevant date of the document, enables it to be prepared and separated or, in the case of a product of nature, only to be separated.

Implicit disclosures: The lack of novelty is considered implicit if, in carrying out the teaching of the state-of-the-art document, the skilled person would inevitably arrive at a result falling within the terms of the claim.

A general teaching or disclosure does not as a rule deprive a more specific invention of its novelty. Specific disclosures, on the other hand, do deprive more general inventions of novelty.

In the same vein, when an independent claim is novel, all of the dependent claims it incorporates by reference are also novel. Conversely, the invalidation of an independent claim for lack of novelty does not affect its dependent claims, since they incorporate features that may not be disclosed in the state of the art.21 This rule is also applicable to inventive step.

What is known as the “two-lists principle” is also important in this context. In determining the novelty of a selection of elements, it has to be decided whether the elements are disclosed individually (concretely) in what is alleged to be anticipatory. A claim consisting of a selection from a single list of previously disclosed elements must not be considered novel. But if the specific combination of features claimed must be selected from two or more lists of a certain length, then that combination not specifically disclosed in the state of the art, must be considered novel.

12.4.1.1.2 Inventive step

Article 81 of LP-2015 provides that “an invention is considered as involving an inventive step if, having regard to the state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art.” In determining the state of the art, however, patent applications not published before the relevant date, as referred to in Article 6(3) of LP-2015, are not taken into account.

The Supreme Court has clarified the following:

The criterion for this requisite inventive step is whether the skilled person, working from earlier (state-of-the-art) descriptions and their own knowledge, finds it obvious to obtain the same result, without applying their ingenuity, which indicates that there is no inventive step.22

In practice, Spanish courts follow the problem-solution approach adopted by the EPO Boards of Appeal to assess inventive step as well as novelty. While recognizing that other methods could be used to assess inventive step and avoid an ex post facto analysis, the Supreme Court has explicitly admitted the validity of this approach to inventive step for use in civil proceedings.23

As defined in the Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, this approach consists of three main stages:24

- 1. determining the “closest prior art”

- 2. establishing the “objective technical problem” to be solved, and

- 3. considering whether or not the claimed invention, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person.

The point bears repeating, using the Supreme Court’s succinct description of this method:

First identify the state of the closest prior art; then identify the objective technical problem to be solved; and finally, consider whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the art given the closest prior art and the objective technical problem.25

12.4.1.1.2.1 The closest prior art document

The closest prior art document is that which, in one single reference, discloses the combination of features that constitutes the most promising starting point for a development leading to the invention. In selecting the closest prior art, the first consideration is that it must be directed to a similar purpose or effect as the invention, or at least belong to the same or a closely related technical field as (the technical field of) the claimed invention. In practice, the closest prior art is generally that which corresponds to a similar use and requires the minimum of structural and functional modifications to arrive at the claimed invention.

When judges hear civil invalidation proceedings, the principle of coherence obliges them to respond to an invalidation request, as argued by the party filing it, in accordance with Article 218.1 of the LEC, which provides that “The judgments must be clear, precise and coherent with the claims and with the other pleas of the parties, as deduced in due time during the proceedings.”

But unlike what happens in a patent office, where the document representing the most promising starting point is selected by the examiner, in a court it is the parties who select such documents.

What often happens is that parties propose several documents for examination. In that case, the court can meet the coherence obligation by assuming that the skilled person would reject documents if no more promising than others as starting points. The court can then analyze the starting point as argued by the parties without analyzing every document they propose, rejecting as many as the patent owner can demonstrate are not as promising as what he has proposed.

The Guidelines for Examination in the EPO26 state the following on this point:

In some cases, there are several equally valid starting points for the assessment of inventive step, e.g. if the skilled person has a choice of several workable solutions, i.e. solutions starting from different documents, which might lead to the invention. If a patent is to be granted, it may be necessary to apply the problem-solution approach to each of these starting points in turn, i.e. in respect of all these workable solutions.

But the Guidelines also qualify this statement, as follows:

However, applying the problem-solution approach from different starting points, e.g. from different state-of-the-art documents, is only required if it has been convincingly shown that these documents are equally valid springboards.27

12.4.1.1.2.2 The objective technical problem

The objective technical problem needs to be formulated by first comparing the invention with the closest prior art and then identifying the changes necessary to achieve the technical differences offered by the claimed invention. This means first identifying the differences between the prior disclosure and the claim, and then deriving the technical effect of those differences.

Once the closest prior art has been identified, the second step, taking the problem-solution approach, is to identify the objective technical problem, which means starting with the document representing the prior art closest to the claim at issue and identifying the structural and functional technical differences between what is disclosed in that document and the claim at issue. Once those distinguishing features have been identified, their technical effect is determined and used as the basis for formulating the objective technical problem.

As a general rule the objective technical problem is formulated based on the problem that the patent claim at issue, according to its description, has solved. But if the examination reveals that the problem described has not been solved, or properly framed in the prior art, then the objective technical problem solved by the patent claim must be identified.28 This situation can arise when the challenging party proposes a closest prior art document different than the one on which the patent-granting decision was based.

If the court considers that the closest prior art document or objective technical problem cannot be applied as proposed by the challenging party, the logical course is to dismiss the petition for invalidation, since what is up to the court in a civil case is merely to assess the claim’s validity based on the allegations of the parties, not to re-examine the requirements for patentability.

12.4.1.1.2.3 The obviousness test

Once the closest prior art and objective technical problem claimed to be solved by the invention have been determined, the next step is to assess whether or not the solution offered by the invention is obvious to the person skilled in the art.

This assessment entails a test referred to as the “could-would approach”. According to the Guidelines for Examination in the EPO,29 the question to be answered in this third stage is whether there is any teaching in the prior art as a whole that would (not simply could, but would) have prompted the skilled person, faced with the same objective technical problem, to modify or adapt the closest prior art while taking account of that teaching, thereby arriving at something falling within the terms of the claims and thus achieving what the invention achieves.30

The Supreme Court has stated that:

in assessing whether an invention is obvious, the skilled person does not consider documents or prior rights in an isolated manner, as must be done in assessing novelty, but rather combines them to determine whether the prior information available is sufficient to enable them to reach the same conclusions without need for the information disclosed by the inventor.31

In Judgment No. 334/2016, of May 20, 2026, however, the Supreme Court states that:

The origin of a particular combination is contingent upon an assessment of what was suggested or obvious for the average skilled person, bearing in mind that assessing obviousness often means determining what specific prior rights must be combined to show that the invention would be obvious for an average skilled person with the knowledge available as of the priority date.32

12.4.1.2 Insufficiency of the description

Article 27(1) of LP-2015 provides that “The invention shall be described in the patent application in a sufficiently clear and comprehensive manner to enable a person skilled in the art to carry it out”, failing which, per the patent is invalid.33

The Supreme Court, without calling them binding, has cited three types of considerations by the EPO Boards of Appeal in this area:

- i) First, the occasional failure of a procedure to deliver the results claimed does not affect its reproducibility if only a few attempts are necessary to turn the failure into a success, provided those attempts remain within reasonable limits and do not require an inventive step (T 931/91).

- ii) Second, reproducibility is not affected if the selection of inputs for different parameters is a routine exercise and/or if additional information is provided using examples in the description (T 107/91). In case T 764/14, the Chamber concluded that the skilled person was capable, based on common general knowledge and in the corresponding routine variation of experimental conditions, of supplementing the information contained in paragraph 0031 of the patent at issue and therefore of determining the input concerned, possibly with some uncertainty but without an undue burden [...].

- iii) And in addition, “the EPC does not require that it be possible for the claimed invention to be executed with a few additional undisclosed steps. The only essential requirement is that each of those additional steps be so obvious to the skilled person that, in the light of their common general knowledge, a detailed description of those steps would be superfluous (T 721/89).”34

In the application of this cause of invalidity,

The skilled person is the same as the one we would have to use to assess inventive step. In Judgments No. 334/2016, of May 20, 2016 and No. 532/2017, of October 2, 2017, we [the Supreme Court] clarified that “the skilled person” is a hypothetical specialist in the technical field corresponding to the invention at issue, possessed of common general knowledge in that subject matter and having access at the relevant date to related, state-of-the-art information – and in particular to the documents in the “prior art search report”. This person has more expert knowledge about the technical problem area than about any particular solution. They are not a creative, lack special ingenuity (they are not an inventor) and are influenced by prejudices common to the time in the state of the art concerned.35

12.4.1.3 The addition of subject matter

Article 102(1)(c) of LP-2015 mentions as a cause of invalidation cases where the subject matter of a patent “goes beyond the content of the patent application as filed […]”.

This cause of invalidity flows from the prohibition in Article 48(1) of LP-2015, similar to that contained in Article 123 of the EPC, which establishes the following general rule:

With the exception of those cases involving rectification of obvious errors, the applicant may amend the claims in their application at any stage of the grant procedure where it is specifically permitted under the present Law, and subject to what is regularly established.

Article 48(5) of LP-2015 limits the possibility of amending claims where their “subject matter goes beyond the content of the patent application as initially filed.”

The Supreme Court cited another criterion applied by the EPO Boards of Appeal in this area, again without binding effect:

‘The content of the application as filed’ refers to information disclosed by the entire application, understood as including the claims, description and drawings.36

Assessing this cause of invalidation logically requires a comparison between the claims in the patent application and those in the patent as granted. The claim is invalid if new protected subject matter has been added – if it incorporates new technical features that the skilled person would not consider to be clearly and directly derived from the application.37

12.4.1.4 The expansion of protection

With reference to the patent granted, as in the previous instance, Article 48(6) of LP-2015 prohibits amending the granted patent during the opposition or, as the case may be, the limitation procedure, so as to extend the protection conferred by the patent. Article 102(1)(d) of LP-2015 provides for the invalidation of a claim “when the protection conferred by the patent has been expanded after being granted”. Just as in the case of added content above, the patent originally granted must be compared with the amendment made after an opposition or limitation procedure conducted subsequent to its grant.

The Supreme Court explained that:

Limitation is an amendment made to claims as provided for in Article 105 of LP-2015 and Article 105a of the EPC. Limitation can therefore neither add new subject matter for protection (Article 48(5) of LP-2015 and Article 123(2) of the EPC), nor expand the scope of protection (Article 48(6) of LP-2015 and Article 123(3) of the EPC).38

12.4.1.5 Patent registered by a person not entitled to obtain it

Article 10(1) of LP-2015 begins as follows: “The right to a patent shall belong to the inventor or to their successors in title, and it shall be transferable by any of the means recognized in the Law.” This means that the inventor can apply for registration or transfer of their patent rights, but if the patent is granted to a person not entitled to obtain it, then such person who is so entitled may claim transfer of ownership, per Article 12(1) of LP-2015, or seek invalidation of the patent per Article 102(1)(e) of LP-2015.

12.4.2 The effects of invalidity

12.4.2.1 Partial invalidity of a patent

A claim is either invalid or valid in its entirety. If the invalidity affects only part of a claim, the claim can be limited in accordance with Article 102(2) of LP-2015, but only the owner can propose such limitation (Article 103(4) of LP-2015). The court cannot limit a claim through partial invalidation. It can only invalidate the claim in its entirety. In referring to total or partial invalidity of a patent, Article 104(5) of LP-2015 speaks of invalidating all or some of its claims, but not of partially invalidating a single claim. This was better explained in Article 112(2) of LP-1986:

Where the causes of invalidation only affect part of the patent, partial invalidation shall be declared through annulment of the claim or claims affected by those causes. Partial invalidation of a claim may not be declared.

Now, while the earlier explicit provision has been rescinded, the rule preventing partial invalidation of a claim still applies. If a cause of invalidity partially affects a claim, it is up to the owner to limit it. If the owner does not do so, the judge will have to declare the entire claim invalid.39

12.4.2.2 The ex tunc effects of invalidation

Article 104(1) of LP-2015 provides that:

A declaration of invalidation shall imply that the patent has never been valid and that neither the patent nor its original application have had any of the effects provided for in Title VI of the present Law, to the extent that invalidation has been declared.

Without prejudice to compensation for damage and prejudice that may be due when the owner of the invalidated patent has acted in bad faith, according to Article 104(3) of LP-2015,

The retroactive effect of invalidation shall not affect the following:

- a) Decisions on infringement of the patent that have become res judicata and have taken place prior to the declaration of invalidation.

- b) Contracts concluded before the declaration of invalidation, to the extent that they were executed prior to the declaration. However, for reasons of equity and to the extent justified by the circumstances, restitution of the amounts paid under the contract may be claimed.

Once it has become final, the declaration of invalidation of a patent shall become res judicata in respect of all persons.40

12.4.3 Standing to bring invalidation proceedings

Since invalidation proceedings can be exercised by anyone with a legitimate interest in doing so, such proceedings are termed public by law,41 unless brought by a person not authorized to do so, in which case such standing is reserved for persons able to claim ownership.42

An action for invalidation may be brought during the entire validity period of a patent and during the five years after the expiry of the rights.43

12.4.4 Passive standing

An action for patent invalidation must be brought against its registered owner and communicated to all persons owning equitable rights in the patent registered in the Patent Registry, so that they may take part in the proceedings.44

12.4.5 Limitation of the patent during invalidation proceedings

During the invalidation proceedings, Article 103(4) of LP-2015 permits the patent owner to “limit the scope of the patent by amending the claims” in order to defeat any alleged grounds for invalidation. “The proceedings will then be based on the patent as so limited.”

It must be recalled that limitation can result neither in the addition of subject matter, as explained earlier, nor expansion of the scope of protection for the claim limited. As a first condition for a limitation to be ultimately effective, the limits must not be exceeded, and as a second, the amended text of the claim must overcome the alleged cause of invalidity.

12.4.6 Jurisdiction for invalidation proceedings

Civil courts will in all cases have jurisdiction for invalidation proceedings based on the causes mentioned.

12.4.6.1 Appeals against SPTO patent decisions

SPTO decisions with respect to national patents are administrative decisions that may be appealed before national courts. If the ground for challenging a patent is a violation of the administrative rules governing the granting process, the Administrative Courts have jurisdiction for the dispute.45 However, since the enactment of Organic Law No. 7/2022, the civil sections specialized in commercial cases in the Provincial Courts have jurisdiction for actions against violations of substantive provisions of patent law.46

12.4.6.2 Invalidation proceedings before civil courts specialized in commercial matters

If an SPTO decision granting a patent is not challenged by any interested party, through the opposition procedure, within a period of six months,47 the administrative decision will become final and the interested parties may only bring an action for invalidity of the patent before the specialized commercial courts.48 This claim may be asserted by way of action or by way of defense. If obtained by way of judicial action, a declaration of invalidity produces effects in respect of all persons, as provided in Article 104(4) of LP-2015, and the patent registration is canceled. If obtained only by way of defense, it produces effects only between the parties.

12.4.7 The burden of proof in invalidation proceedings

Once a patent has been granted by a final administrative decision, it is not the owner who must prove that the requirements for patentability have been met. It is rather up to a plaintiff bringing action for invalidation to prove that the challenged claim is flawed on grounds for invalidation. According to Article 102(1)(a) of LP-2015,

A patent shall be declared invalid in the following cases: (a) when it is proved that, in respect of the subject matter of the patent, one of the conditions of patentability contained in Title II of the present Law, has not been met.

If it must be proved that one of the conditions of patentability has not been met, that burden logically falls on the challenger, not the patent owner.49

12.5 Patent infringement

The patent system offers legal certainty to inventors operating in a given technology sector. Those who register their inventions enjoy the exclusive right to exploit them for a determined period of time. Patents are also a way to make public an innovation that might otherwise remain unknown. A patent title determines what constitutes an invention protected by exclusive rights while also enriching the corpus of human knowledge and contributing to social progress. A patent delineates what must be respected during its period of duration so that actors in the market can avoid infringing the protected rights of others. Those interested in using protected technology can seek authorization to do so from its inventor, in exchange, as the case may be, for the price of licensing it. Or alternatively, they can opt to solve the same technical problem using means already available in the public domain or attempt through their own research and using their own resources to devise a different creative solution. Conversely, using a patented solution without permission from the patent owner constitutes infringement, subject to legal prosecution.

If a patent right holder or legitimate licensee detects the presence in a market of competing products or services they consider to be infringing their exclusive rights, they can deploy legal mechanisms in defense of their legitimate interests. Disputes not resolved by alternative means can then lead to litigation in the courts.

12.5.1 Claim construction

The subject matter of a patent is a crucial starting point in understanding the scope of protection provided by public authorities for an exclusive right to the invention concerned. This is part of what makes the claims made in a patent so important.

The protected content of a patent consists of one or more claims, which define the subject matter of the patent for which exclusive rights are sought. These claims take concrete form in an invention’s technical features (structural and functional). They consist of one or more elements, the interrelationship between them and the technical effect they produce as the purpose of the invention.

There are various kinds of claims. They may relate to a physical entity (a product, substance or mixture), a device (an apparatus or machine) or even a system (a series of devices working together). A claim can also consist of an activity (procedures or methods for the manufacture of a product or even new uses for a product, such as previously known substances or compositions used as a medicine or for new therapeutic applications) (see Articles 6(4) and 6(5) of LP-2015). Claims relating to a physical entity protect the product or device in its entirety, and therefore convey the right for their owners to prevent third parties from exploiting them without the owner’s consent. The owners can thus prohibit others from manufacturing, offering, commercializing (using, importing or possessing for those purposes) the patented product (mechanical, electrical, nutritional, chemical, pharmaceutical, phytosanitary, microbiological, biological, genetic) irrespective of the procedure used to obtain it (since the claims relate to a physical object). Claims made for a procedure protect the operations used to transform one or more initial substances into one or more final products, enabling their holders to prevent only use of the patented procedure and offers thereof for use. Also, a claim for a procedure to obtain a product protects only the product obtained directly from that procedure – not manufacture of the product using a different procedure.

A claim is expressed as an explanation of positive features. Exceptionally, however, the scope of a claim may be limited in a negative manner by means of a disclaimer, so that one element is explicitly excluded from the claimed protection.

All patents must contain at least one independent claim – the claim that defines the entity or activity that constitutes a solution to a technical problem as identified in the application. The independent claim must clearly specify each and every one of the features necessary to define the invention – unless such features are implicit in the generic terms used.

The patent may include more than one independent claim in the same category (product, procedure, device or use), but must comply with the requirement of “unity of invention”. That means that the claims must have subject matter in common forming a single general inventive concept. It must otherwise be divided among different patents.

The independent claim can (optionally) then be followed by one or more dependent claims, structured so as to add one or more technical features. This results in a scope more limited than the claim on which they depend but without altering the essential nature of the invention. Dependent claims can embody different, more specific versions of the invention.

The claims must be clear, concise and based on the description.50 They provide the basis for determining whether the patentability requirements (novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability) have been met. The content and form of claims is regulated precisely (see Article 7 of the Implementing Regulations for the Law on Patents, approved by Royal Decree No. 316/2017, of March 31, 2017 (Implementing Regulations for the Law on Patents)51, regarding the national patents and the Implementing Regulations to the Convention on the Grant of European Patents, with reference to national patents). Under these regulations, claims must include, first of all, a preamble indicating the subject matter of the invention and the precise technical features used to define the elements claimed, which combine to constitute the state of the art. Claims must then include a section explaining the technical features (characterization section), which combined with the content of the preamble represents what the patent is intended to protect. Whereas the preamble provides the context and characterizes the invention, it is the characterization section that contains the actual inventive elements.52 That is where the technical features to be protected, presented as novel, are explained.

Patents are not the only industrial property instruments for protecting inventions under Spanish law. LP-2015 provides for two others. The first, utility models, require novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability but are considered “minor” inventions. They offer a configuration, structure or composition to give an object or product some practically appreciable advantage for use or manufacture (Articles 2 and 137 of LP-2015). The second, supplementary protection certificates, are for medicines and plant protection products. For a maximum duration of five years they provide the same protection as a patent for the active ingredients or combinations of active ingredients of medicines or plant protection products after patent protection expires, to compensate for the time required to complete the formalities entailed in obtaining marketing approval (Articles 2 to 6 of Regulation (EC) 469/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 May 2009,53 in conjunction with Articles 45 to 47 of LP-2015). The general analysis of what constitutes an infringement of exclusive rights also applies to these titles, albeit with certain particularities in each case.

12.5.2 Patent infringement disputes

Patent owners considering legal action to defend their rights must first clearly identify which of their claims may have been infringed. An error sometimes committed in this regard is losing sight of what the plaintiff’s patent actually protects and what rights it actually confers. A strategy to avoid is focusing on the properties of the object, product or substance the plaintiff is commercializing, as it should not be assumed that they all correspond to the features of the invention as registered. It is important to bear in mind that in patent litigation, the latter and not the former is what matters. what needs to be perfectly clear in the complaint is what the plaintiff has registered specifically and how it has been unduly affected by the activities of a third party. Cases are lost when this basic point is forgotten.

A second important point in filing these complaints is to identify the features of what the defendant has been manufacturing or commercializing. This is precisely what should be compared with what is claimed in the patent. What the defendant may have subsequently registered is not relevant in this context, as infringement disputes are not about comparing titles according to legal priority. What matters is to verify whether the actions of the defendant constitute an infringement of the priority right registered by the plaintiff.

The best approach to these disputes is to accompany the complaint with an expert opinion54 on related technical issues, with which the judge – however specialized the court may be in the subject matter concerned – may well be unfamiliar.55 The opinion should focus first on the scope of the claims allegedly infringed, and then on how the defendant’s activities infringed them.

To clearly assess whether the conduct of the defendant constitutes an infringement of the plaintiff’s patent, the protected subject matter of the patent must be determined according to the patent’s definition of the exclusive right.56 This means delving into a legal analysis that must be based on properly structured technical information. The plaintiff’s legal position will not otherwise be sufficiently robust.

Precise specification of what constitutes the patent’s subject matter will be of fundamental importance in deciding whether infringement has occurred. It must be remembered here that protected subject matter is defined by a patent’s claims as informed by the description and drawings accompanying them. In bringing action against an infringement, the first step is to determine the scope of patent protection.57 This is because, as stressed by the Spanish Supreme Court, patent claims perform two functions. First, they define the subject matter to be protected by indicating the technical features of the invention necessary to execute the procedure or define the product concerned and thereby solve the technical problem identified in the specifications. And second, they determine the extent of protection conferred by the patent or patent application, taking into account the accompanying description and drawings.

The subject matter of the invention must be determined based on an analysis of the technical features in the characterization section, which must relate to the content of the preamble that introduces and contextualizes the invention. That permits what is novel about the invention to be identified, and thus for the extent and limits of the patent protection to be outlined. But to delineate more precisely where that protection is relevant to the case, it must be determined where the patent is exclusive and interpret the claims infringed to ascertain their technical and legal meaning in the context of the case. It is important to maintain the right legal balance in performing this analysis. The interpretation of claims should be neither too exorbitant nor too literal. The key is to find the right balance between equitable protection for the applicant and a reasonable degree of certainty for third parties (as described in the Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69 EPC). Spanish case law in this area58 admits no need for a strictly literal interpretation, allowing for a more intuitive approach, to find the true meaning behind the content of a claim. In determining the scope of patent protection, Spanish rulings have also tended to admit and factor in arguments based on the history behind patent applications and grants, including disclaimers, limitations and other steps taken by applicants in their interactions with patent offices.

12.5.3 Opposition by defendants

It is obviously not infrequent for patent owners bringing actions against infringement of their rights to encounter defendants mounting an offensive strategy against those rights. They may for instance file counterclaims for the patent to be declared invalid or subject to exceptions.59 This shifts the argument to an issue prior to the alleged infringement: whether the requirements for patentability of the invention were initially met or there are any other legal causes of invalidity that may be alleged.60 The decision process for handling those kinds of disputes has been covered above, so we turn next to the alleged infringement.

An argument the defendant may raise in that connection is that of having been authorized to use the patent, which calls for an analysis of the origin and scope of such authorization to determine whether the defendant’s conduct was in fact justified. The defendant might also argue that their conduct was not an infringement because it did not encroach on the scope of the exclusive right conferred by the patent.

12.5.4 Literal infringement

The defendant’s conduct can be considered infringement if the technical solution addressed by the products and services they offer is precisely the same as what has been included in the characterization section of the patent owner’s claims. Only if that can be demonstrated can the defendant’s conduct be considered a literal infringement of the plaintiff’s exclusive rights. If the patent includes multiple claims, such encroachment on any constitutes infringement, since each claim represents a legally protected invention (which must nonetheless comply with the principle of inventive unity). If the claims are structured more broadly, with various dependent claims, encroachment on any of those can also be successfully impugned as infringement.

For the court to rule that infringement has occurred, a wealth of carefully structured technical information must be provided to the judge to demonstrate that each and every one of the technical features registered in the patent are present in the defendant’s product or service. It is up to the plaintiff to provide that information and meet a burden of proof appropriate for the circumstances with sufficient supporting evidence. That effort may well fail, however, if the expert opinion provided to the court does not meticulously compare the registered claims with the specific characteristics of the object manufactured, commercialized or used by the defendant. The same is true if the opinion neglects to cite the text of the patent and concentrates instead on comparing the objects, materials or products manufactured or commercialized by each party, rather than the content registered for the invention. That is not the right approach to analyzing potential patent infringement. It does not provide the judge with the technical criteria needed to determine whether exclusive rights have been infringed. Mere intuition does not suffice.

A finding that an exclusive patent right has been infringed can be obtained only by means of a legal effort to rigorously compare registered claims with the object manufactured, commercialized or used by the defendant, and only if the defendant’s actions fit within the scope of protection for any of the claims.61 It will be concluded that the defendant has infringed the plaintiff’s exclusive rights if the defendant’s products or services simultaneously embody all of the elements contained in one of the patent’s claims and each and every one of the technical features protected by the registered claims under the patent. The manufacture, sale or use of objects considered to be a reproduction of technical features registered by the plaintiff will permit the protection legally afforded by patents to be invoked.62

A finding of patent infringement requires more than a general comparison between the invention claimed and a competing version of that invention. A much more rigorous element-by-element comparison must be made between the two. Only when all the technical features of the patented invention have been reproduced by the impugned activities can it be considered that the rights conferred by the patent have been infringed (the rule of the simultaneity of all elements must have been satisfied). Courts in Spain may not invoke the “essentiality” doctrine, now considered obsolete, to rule that a patent has been infringed. Dating back to LP-1986, the relevant comparison has not been between the “essence” of the patent and the product or service at issue, but between each element, one by one, to demonstrate that each and every one of the technical features of the object protected by the patent have been reproduced identically or equivalently by the allegedly infringing object.

The mere fact that someone has acted in the light of another person’s patent does not constitute infringement, unless the technical features claimed in the patent have been reproduced element by element. If a different solution is offered for the problem the patent is intended to solve, such that any of the elements of the invention claimed has not been reproduced, either because use has been made of an innovative method – or an alternative method within the state of the art but not protected by patent – then no exclusive right has been infringed and the infringement action must fail.

12.5.5 Infringement by equivalence

In following the approach described above, it is important to prevent infringement from going unpenalized through a subterfuge: that of introducing irrelevant variations in a product or process to avoid the appearance that patent claims have been duplicated.63 It is therefore important to bear in mind what was mentioned earlier about the interpretation and scope of claims. Infringement by equivalence is where an opposing party avoids identically reproducing every element of a patent claim by replacing one of its characterizing elements with another that is clearly equivalent. Spanish legislation makes it explicitly clear that patents also protect inventions where apparent discrepancies in an element are found in reality to be equivalent.64 Such equivalence means that infringement has in fact occurred, carrying the same legal consequences as literal infringement.

When the comparison of elements is performed as described earlier, attention must be paid to whether a variation in an element that initially appears not to reproduce an element in a patent claim is not in reality a substantial variation from the perspective of a person skilled in the art. It is infringement – not literally but by equivalence (although the legal effect is the same) – if a function, the way it is performed, and the results obtained in solving a problem targeted by a patented claim are essentially replicated. Hence the crucial importance of patent descriptions. The proviso in all of this is that it must be obvious to the skilled person that the variation observed in the element concerned falls within the patent’s scope of protection, based on its claims as interpreted in the overall context of the patent, including its accompanying description and drawings.

As a general rule, an element must be considered equivalent to an element of a claim if in its context it performs the same function to produce the same results from the perspective of a person skilled in the art. However, some additional factors must be considered in reaching that judgment. These include whether the skilled person – from the perspective of the priority date (if earlier, so as to avoid ex post facto judgments) – would have considered the element as falling outside the patent’s scope of protection based on its description, drawings and claims. Consideration must also be given to whether the element would correspond to the prior art or be obvious from the perspective of the prior art. And yet another point to consider is whether the patent owner expressly and unequivocally excluded the element from the claim during the application process to avoid an objection from the examiner based on the prior art.

An approach frequently used to determine this issue of equivalence is the so-called triple identity test, which consists of analyzing whether the element performs the same function, uses the same modus operandi and produces the same result. While particularly useful for mechanical patents, this method may prove inadequate for other types of patents (for chemicals, medicines, etc.) which must be assessed based on a concrete case and an objective application of the rules described above – and from the perspective of a person skilled in the art. It is especially important in this context not to confuse this hypothetical “person” with an expert trial witness, the former being a legal concept and a function of the technical sector concerned, such that the point of reference must be determined according to the particularities of the case.

Another method used in assessing equivalence or non-equivalence comes from British case law (the “Catnic” and “Improver” cases) and is now also used in Spanish forensic practice. It consists of asking and answering up to three questions in sequential order until the situation is clarified. First, does the variant used by the defendant substantially alter the functioning of the invention described in the plaintiff’s patent? If it does, there is no equivalence. If it does not, the process continues with the second question: would the proposed alternative have appeared obvious to the skilled person reading the patent at the time of its publication? If it entails inventive step, there is no equivalence. If it would have appeared obvious, the third question is asked: in the opinion of the skilled person, having read the text of the claims and the patent description, did the patent owner intend to adhere strictly to the terms of the claim, as essential to the invention?

In any case – and this cannot be stressed too often – it is indispensable to methodically analyze, through element-by-element comparison between the patent and the good or service at issue, whether infringement by equivalence has been committed. To be rigorous, it is not acceptable to settle for general considerations about the overall invention. It is necessary to determine precisely what specific element is being substituted by equivalence for an element specified in the patent claim.

On the other hand, an element cannot be considered equivalent if the patent owner made the corresponding element in the patent claim subject to a disclaimer or limitation during the application process.

12.5.6 Indirect infringement

Patent protection can extend even beyond the areas discussed above. Patent owners also have the right to prevent third parties from delivering or offering to deliver to persons not authorized to exploit it, without the owner’s consent, means of exploiting a patented invention relating to an essential element thereof, knowing, or under circumstances making it obvious, that those means can effectively serve, and are intended to serve, that purpose. This is what is known as indirect or contributory infringement.65

Three requirements must be met for an act to be considered indirect infringement:

- 1. the alleged infringer must have provided means necessary to put an essential element of the patent into practice;

- 2. the person acquiring those means must not be legally authorized to exploit the patent; and

- 3. the infringer must have known, or circumstances must have made it obvious, that the means provided would permit, and were intended to permit, the invention to be put into practice by someone not authorized to do so.

The circumstances prevailing in the case can be assessed by analyzing various factors. Such an analysis might reveal, for example, that the means offered had no other use than for infringement; that a given volume of sales could be generated using the means offered to work the invention; or that information or instructions were provided to the defendant on how to operate the invention and any other data that may prove relevant in practice.

Such means need not be intended for use in the same country from which they are offered for their provision to constitute indirect infringement.

In some cases, the provision of such means may not provide a sufficient basis for a finding that indirect infringement has been committed. One such case is where the means provided consist of products purchasable for purposes other than patent infringement – unless the party providing them induces the receiving party to use them for such infringement.66 Where such products are currently available on the market it will be necessary to show that the indirect infringer has induced direct patent infringement for their conduct to be considered unlawful. This line of argument is an example of how a patent can be defended without expanding its scope of protection. It should not, however, have the effect of preventing such products from being supplied for legal uses, unrelated to patent infringement.

12.6 Judicial patent proceedings and case management

12.6.1 Key features in patent proceedings

Judicial proceedings relating to patents are handled in Spain within the civil jurisdictional division, and more specifically by specialized commercial courts.

The basic rules governing such proceedings are contained in LP-2015, which dedicates Title XII to “Jurisdiction and Procedural Regulations”.67 Also applicable, for matters not covered in LP-2015, are procedural rules contained in the LEC.

One of the more noteworthy characteristics of patent-related litigation in Spain is that the cases are adjudicated by specialized civil courts.

Beyond patent infringement, invalidation and declaration of non-infringement actions,68 specialized commercial courts have recently been assigned jurisdiction for appeals against SPTO decisions that mark the exhaustion of available administrative remedies for industrial property disputes. Among others, such decisions include patent refusals, oppositions, limitations and the validation of European patents. Jurisdiction for reviewing such SPTO decisions was reassigned from the country’s administrative courts69 to civil courts by Organic Law No. 7/2022. The type of judicial proceedings and the court competent to conduct them varies according to the matter in dispute, whether it be patent infringement, invalidation, declaration of non-infringement actions or appeals against SPTO decisions.

As discussed in greater detail below, patent invalidation, patent infringement and declaration of non-infringement actions are adjudicated in the first instance by ordinary commercial courts,70 as regulated by the LEC, with significant particularities introduced by Title XII of LP-2015.